Antarctica

Antarctica (/ænˈtɑːrktɪkə/ ⓘ) is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest continent, being about 40% larger than Europe, and has an area of 14,200,000 km2 (5,500,000 sq mi). Most of Antarctica is covered by the Antarctic ice sheet, with an average thickness of 1.9 km (1.2 mi).

Antarctica is, on average, the coldest, driest, and windiest of the continents, and it has the highest average elevation. It is mainly a polar desert, with annual precipitation of over 200 mm (8 in) along the coast and far less inland. About 70% of the world's freshwater reserves are frozen in Antarctica, which, if melted, would raise global sea levels by almost 60 metres (200 ft). Antarctica holds the record for the lowest measured temperature on Earth, −89.2 °C (−128.6 °F). The coastal regions can reach temperatures over 10 °C (50 °F) in the summer. Native species of animals include mites, nematodes, penguins, seals and tardigrades. Where vegetation occurs, it is mostly in the form of lichen or moss.

The ice shelves of Antarctica were probably first seen in 1820, during a Russian expedition led by Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen and Mikhail Lazarev. The decades that followed saw further exploration by French, American, and British expeditions. The first confirmed landing was by a Norwegian team in 1895. In the early 20th century, there were a few expeditions into the interior of the continent. British explorers Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton were the first to reach the magnetic South Pole in 1909, and the geographic South Pole was first reached in 1911 by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen.

Antarctica is governed by about 30 countries, all of which are parties of the 1959 Antarctic Treaty System. According to the terms of the treaty, military activity, mining, nuclear explosions, and nuclear waste disposal are all prohibited in Antarctica. Tourism, fishing and research are the main human activities in and around Antarctica. During the summer months, about 5,000 people reside at research stations, a figure that drops to around 1,000 in the winter. Despite the continent's remoteness, human activity has a significant effect on it via pollution, ozone depletion, and climate change. The melting of the potentially unstable West Antarctic ice sheet causes the most uncertainty in century-scale projections of sea level rise, and the same melting also affects the Southern Ocean overturning circulation, which can eventually lead to significant impacts on the Southern Hemisphere climate and Southern Ocean productivity.

Etymology

The name given to the continent originates from the word antarctic, which comes from Middle French antartique or antarctique ('opposite to the Arctic') and, in turn, the Latin antarcticus ('opposite to the north'). Antarcticus is derived from the Greek ἀντι- ('anti-') and ἀρκτικός (arktikos, 'of the Bear [Ursa Major], northern'). The Greek philosopher Aristotle wrote in Meteorology about an "Antarctic region" in c. 350 BCE. The Greek geographer Marinus of Tyre reportedly used the name in his world map from the second century CE, now lost. The Roman authors Gaius Julius Hyginus and Apuleius used for the South Pole the romanised Greek name polus antarcticus, from which derived the Old French pole antartike (modern pôle antarctique) attested in 1270, and from there the Middle English pol antartik, found first in a treatise written by the English author Geoffrey Chaucer.

Belief by Europeans in the existence of a Terra Australis—a vast continent in the far south of the globe to balance the northern lands of Europe, Asia, and North Africa—had existed as an intellectual concept since classical antiquity. The belief in such a land lasted until the European discovery of Australia.

During the early 19th century, explorer Matthew Flinders doubted the existence of a detached continent south of Australia (then called New Holland) and thus advocated for the "Terra Australis" name to be used for Australia instead. In 1824, the colonial authorities in Sydney officially renamed the continent of New Holland to Australia, leaving the term "Terra Australis" unavailable as a reference to Antarctica. Over the following decades, geographers used phrases such as "the Antarctic Continent". They searched for a more poetic replacement, suggesting names such as Ultima and Antipodea. Antarctica was adopted in the 1890s, with the first use of the name being attributed to the Scottish cartographer John George Bartholomew.

Antarctica has also been known by the moniker Great White South, after which British photographer Herbert Ponting named one of his books on Antarctic photography, possibly as a counterpart to the epithet Great White North for Canada.

Geography

Positioned asymmetrically around the South Pole and largely south of the Antarctic Circle (one of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of the world), Antarctica is surrounded by the Southern Ocean. Rivers exist in Antarctica; the longest is the Onyx. Antarctica covers more than 14.2 million km2 (5,500,000 sq mi), almost double the area of Australia, making it the fifth-largest continent, and comparable to the surface area of Pluto. Its coastline is almost 18,000 km (11,200 mi) long: as of 1983[update], of the four coastal types, 44% of the coast is floating ice in the form of an ice shelf, 38% consists of ice walls that rest on rock, 13% is ice streams or the edge of glaciers, and the remaining 5% is exposed rock.

The lakes that lie at the base of the continental ice sheet occur mainly in the McMurdo Dry Valleys or various oases. Lake Vostok, discovered beneath Russia's Vostok Station, is the largest subglacial lake globally and one of the largest lakes in the world. It was once believed that the lake had been sealed off for millions of years, but scientists now estimate its water is replaced by the slow melting and freezing of ice caps every 13,000 years. During the summer, the ice at the edges of the lakes can melt, and liquid moats temporarily form. Antarctica has both saline and freshwater lakes.

Antarctica is divided into West Antarctica and East Antarctica by the Transantarctic Mountains, which stretch from Victoria Land to the Ross Sea. The vast majority of Antarctica is covered by the Antarctic ice sheet, which averages 1.9 km (1.2 mi) in thickness. The ice sheet extends to all but a few oases, which, with the exception of the McMurdo Dry Valleys, are located in coastal areas. Several Antarctic ice streams flow to one of the many Antarctic ice shelves, a process described by ice-sheet dynamics.

East Antarctica comprises Coats Land, Queen Maud Land, Enderby Land, Mac. Robertson Land, Wilkes Land, and Victoria Land. All but a small portion of the region lies within the Eastern Hemisphere. East Antarctica is largely covered by the East Antarctic Ice Sheet. There are numerous islands surrounding Antarctica, most of which are volcanic and very young by geological standards. The most prominent exceptions to this are the islands of the Kerguelen Plateau, the earliest of which formed around 40 Ma.

Vinson Massif, in the Ellsworth Mountains, is the highest peak in Antarctica at 4,892 m (16,050 ft). Mount Erebus on Ross Island is the world's southernmost active volcano and erupts around 10 times each day. Ash from eruptions has been found 300 kilometres (190 mi) from the volcanic crater. There is evidence of a large number of volcanoes under the ice, which could pose a risk to the ice sheet if activity levels were to rise. The ice dome known as Dome Argus in East Antarctica is the highest Antarctic ice feature, at 4,091 metres (13,422 ft). It is one of the world's coldest and driest places—temperatures there may reach as low as −90 °C (−130 °F), and the annual precipitation is 1–3 cm (0.39–1.18 in).

Geologic history

From the end of the Neoproterozoic era to the Cretaceous, Antarctica was part of the supercontinent Gondwana. Modern Antarctica was formed as Gondwana gradually broke apart beginning around 183 Ma. For a large proportion of the Phanerozoic, Antarctica had a tropical or temperate climate, and it was covered in forests.

Paleozoic era (540–250 Ma)

During the Cambrian period, Gondwana had a mild climate. West Antarctica was partially in the Northern Hemisphere, and during the time, large amounts of sandstones, limestones, and shales were deposited. East Antarctica was at the equator, where seafloor invertebrates and trilobites flourished in the tropical seas. By the start of the Devonian period (416 Ma), Gondwana was in more southern latitudes, and the climate was cooler, though fossils of land plants are known from then. Sand and silts were laid down in what is now the Ellsworth, Horlick, and Pensacola Mountains.

Antarctica became glaciated during the Late Paleozoic icehouse beginning at the end of the Devonian period (360 Ma), though glaciation would substantially increase during the late Carboniferous. It drifted closer to the South Pole, and the climate cooled, though flora remained. After deglaciation during the latter half of the Early Permian, the land became dominated by glossopterids (an extinct group of seed plants with no close living relatives), most prominently Glossopteris, a tree interpreted as growing in waterlogged soils, which formed extensive coal deposits. Other plants found in Antarctica during the Permian include Cordaitales, sphenopsids, ferns, and lycophytes. At the end of the Permian, the climate became drier and hotter over much of Gondwana, and the glossopterid forest ecosystems collapsed, as part of the End-Permian mass extinction. There is no evidence of any tetrapods having lived in Antarctica during the Paleozoic.

Mesozoic era (250–66 Ma)

The continued warming dried out much of Gondwana. During the Triassic period, Antarctica was dominated by seed ferns (pteridosperms) belonging to the genus Dicroidium, which grew as trees. Other associated Triassic flora included ginkgophytes, cycadophytes, conifers, and sphenopsids. Tetrapods first appeared in Antarctica during the Early Triassic epoch, with the earliest known fossils found in the Fremouw Formation of the Transantarctic Mountains. Synapsids (also known as "mammal-like reptiles") included species such as Lystrosaurus, and were common during the Early Triassic.

The Antarctic Peninsula began to form during the Jurassic period (206 to 146 million years ago). Africa separated from Antarctica in the Jurassic around 160 Ma, followed by the Indian subcontinent in the early Cretaceous (about 125 Ma). Ginkgo trees, conifers, Bennettitales, horsetails, ferns and cycads were plentiful during the time. About 80 million years ago, flowering plants became the most diverse groups of plants on the continent. In West Antarctica, coniferous forests dominated throughout the Cretaceous period (146–66 Ma), though southern beech trees (Nothofagus) became prominent towards the end of the Cretaceous. Ammonites were common in the seas around Antarctica, and dinosaurs were also present, though only a few Antarctic dinosaur genera (Cryolophosaurus and Glacialisaurus, from the Early Jurassic Hanson Formation of the Transantarctic Mountains, and Antarctopelta, Trinisaura, Morrosaurus and Imperobator from Late Cretaceous of the Antarctic Peninsula) have been described.

Cenozoic era before present (66–10 Ma)

During the early Paleogene, the Antarctic land bridge continued to connect Antarctica with South America as well as to southeastern Australia. Fauna from the La Meseta Formation in the Antarctic Peninsula, dating to the Eocene, is very similar to equivalent South American faunas; with marsupials, xenarthrans, litoptern, and astrapotherian ungulates, as well as gondwanatheres and possibly meridiolestidans. Marsupials are thought to have dispersed into Australia via Antarctica by the early Eocene.

Around 53 Ma, Australia-New Guinea separated from Antarctica, opening the Tasmanian Passage. The Drake Passage opened between Antarctica and South America around 30 Ma, resulting in the creation of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current that completely isolated the continent. Models of Antarctic geography suggest that this current, as well as a feedback loop caused by lowering CO2 levels, caused the creation of small yet permanent polar ice caps. As CO2 levels declined further the ice began to spread rapidly, replacing the forests that until then had covered Antarctica. Tundra ecosystems continued to exist on Antarctica until around 14–10 million years ago, when further cooling lead to their extermination.

Present day

The geology of Antarctica, largely obscured by the continental ice sheet, is being revealed by techniques such as remote sensing, ground-penetrating radar, and satellite imagery. Geologically, West Antarctica closely resembles the South American Andes. The Antarctic Peninsula was formed by geologic uplift and the transformation of sea bed sediments into metamorphic rocks.

West Antarctica was formed by the merging of several continental plates, which created a number of mountain ranges in the region, the most prominent being the Ellsworth Mountains. The presence of the West Antarctic Rift System has resulted in volcanism along the border between West and East Antarctica, as well as the creation of the Transantarctic Mountains.

East Antarctica is geologically varied. Its formation began during the Archean Eon (4,000 Ma–2,500 Ma), and stopped during the Cambrian Period. It is built on a craton of rock, which is the basis of the Precambrian Shield. On top of the base are coal and sandstones, limestones, and shales that were laid down during the Devonian and Jurassic periods to form the Transantarctic Mountains. In coastal areas such as the Shackleton Range and Victoria Land, some faulting has occurred.

Coal was first recorded in Antarctica near the Beardmore Glacier by Frank Wild on the Nimrod Expedition in 1907, and low-grade coal is known to exist across many parts of the Transantarctic Mountains. The Prince Charles Mountains contain deposits of iron ore. There are oil and natural gas fields in the Ross Sea.

Climate

Antarctica is the coldest, windiest, and driest of Earth's continents. Near the coast, the temperature can exceed 10 °C in summer and fall to below −40 °C in winter. Over the elevated inland, it can rise to about −30 °C in summer but fall below −80 °C in winter.

The lowest natural air temperature ever recorded on Earth was −89.2 °C (−128.6 °F) at the Russian Vostok Station in Antarctica on 21 July 1983. A lower air temperature of −94.7 °C (−138.5 °F) was recorded in 2010 by satellite—however, it may have been influenced by ground temperatures and was not recorded at a height of 2 m (7 ft) above the surface as required for official air temperature records. Antarctica is colder than the Arctic region, as much of Antarctica is over 3,000 m (9,800 ft) above sea level, where air temperatures are colder. The relative warmth of the Arctic Ocean is transferred through the Arctic sea ice and moderates temperatures in the Arctic region.

Winds are strong and persistent.

Antarctica is a polar desert with little precipitation; the continent receives an average equivalent to about 150 mm (6 in) of water per year, mostly in the form of snow. The interior is dryer and receives less than 50 mm (2 in) per year, whereas the coastal regions typically receive more than 200 mm (8 in). In a few blue-ice areas, the wind and sublimation remove more snow than is accumulated by precipitation. In the dry valleys, the same effect occurs over a rock base, leading to a barren and desiccated landscape.

Regional differences

East Antarctica is colder than its western counterpart because of its higher elevation. Weather fronts rarely penetrate far into the continent, leaving the centre cold and dry, with moderate wind speeds. Heavy snowfalls are common on the coastal portion of Antarctica, where snowfalls of up to 1.22 m (48 in) in 48 hours have been recorded. At the continent's edge, strong katabatic winds off the polar plateau often blow at storm force. During the summer, more solar radiation reaches the surface at the South Pole than at the equator because of the 24 hours of sunlight received there each day.

Climate change

Despite its isolation, Antarctica has experienced warming and ice loss in recent decades, driven by greenhouse gas emissions. West Antarctica warmed by over 0.1 °C per decade from the 1950s to the 2000s, and the exposed Antarctic Peninsula has warmed by 3 °C (5.4 °F) since the mid-20th century. The colder, stabler East Antarctica did not show any warming until the 2000s. Around Antarctica, the Southern Ocean has absorbed more oceanic heat than any other ocean, and has seen strong warming at depths below 2,000 m (6,600 ft). Around the West Antarctic, the ocean has warmed by 1 °C (1.8 °F) since 1955.

The warming of the Southern Ocean around Antarctica has caused the weakening or collapse of ice shelves, which float just offshore of glaciers and stabilize them. Many coastal glaciers have been losing mass and retreating, causing net ice loss across Antarctica, although the East Antarctic ice sheet continues to gain ice inland. By 2100, net ice loss from Antarctica is expected to add about 11 cm (5 in) to global sea-level rise. Marine ice sheet instability may cause West Antarctica to contribute tens of centimeters more if it is triggered before 2100. With higher warming, instability would be much more likely, and could double global, 21st-century sea-level rise.

The fresh meltwater from the ice dilutes the saline Antarctic bottom water, weakening the lower cell of the Southern Ocean overturning circulation (SOOC). According to some research, a full collapse of the SOOC may occur at between 1.7 °C (3.1 °F) and 3 °C (5.4 °F) of global warming, although the full effects are expected to occur over multiple centuries; these include less precipitation in the Southern Hemisphere but more in the Northern Hemisphere, an eventual decline of fisheries in the Southern Ocean and a potential collapse of certain marine ecosystems. While many Antarctic species remain undiscovered, there are documented increases in Antarctic flora, and large fauna such as penguins are already having difficulty retaining suitable habitat. On ice-free land, permafrost thaws release greenhouse gases and formerly frozen pollution.

The West Antarctic ice sheet is likely to completely melt unless temperatures are reduced by 2 °C (3.6 °F) below 2020 levels. The loss of this ice sheet would take between 500 and 13,000 years. A sea-level rise of 3.3 m (10 ft 10 in) would occur if the ice sheet collapses, leaving ice caps on the mountains, and 4.3 m (14 ft 1 in) if those ice caps also melt. The far-stabler East Antarctic ice sheet may only cause a sea-level rise of 0.5 m (1 ft 8 in) – 0.9 m (2 ft 11 in) from the current level of warming, a small fraction of the 53.3 m (175 ft) contained in the full ice sheet. With global warming of around 3 °C (5.4 °F), vulnerable areas like Wilkes Basin and Aurora Basin may collapse over around 2,000 years, potentially adding up to 6.4 m (21 ft 0 in) to sea levels.Ozone depletion

Scientists have studied the ozone layer in the atmosphere above Antarctica since the 1970s. In 1985, British scientists, working on data they had gathered at Halley Research Station on the Brunt Ice Shelf, discovered a large area of low ozone concentration over Antarctica. The 'ozone hole' covers almost the whole continent and was at its largest in September 2006; the longest-lasting event occurred in 2020. The depletion is caused by the emission of chlorofluorocarbons and halons into the atmosphere, which causes ozone to break down into other gases. The extreme cold conditions of Antarctica allow polar stratospheric clouds to form. The clouds act as catalysts for chemical reactions, which eventually lead to the destruction of ozone. The 1987 Montreal Protocol has restricted the emissions of ozone-depleting substances. The ozone hole above Antarctica is predicted to slowly disappear; by the 2060s, levels of ozone are expected to have returned to values last recorded in the 1980s.

The ozone depletion can cause a cooling of around 6 °C (11 °F) in the stratosphere. The cooling strengthens the polar vortex and so prevents the outflow of the cold air near the South Pole, which in turn cools the continental mass of the East Antarctic ice sheet. The peripheral areas of Antarctica, especially the Antarctic Peninsula, are then subjected to higher temperatures, which accelerate the melting of the ice. Models suggest that ozone depletion and the enhanced polar vortex effect may also account for the period of increasing sea ice extent, lasting from when observation started in the late 1970s until 2014. Since then, the coverage of Antarctic sea ice has decreased rapidly.

Biodiversity

Most species in Antarctica seem to be the descendants of species that lived there millions of years ago. As such, they must have survived multiple glacial cycles. The species survived the periods of extremely cold climate in isolated warmer areas, such as those with geothermal heat or areas that remained ice-free throughout the colder climate.

Animals

Invertebrate life of Antarctica includes species of microscopic mites such as Alaskozetes antarcticus, lice, fleas (Glaciopsyllus antarcticus), nematodes, tardigrades, rotifers, krill and springtails. The flightless midge Belgica antarctica, the largest purely terrestrial animal in Antarctica, reaches

6 mm (1⁄4 in) in size.Antarctic krill, which congregates in large schools, is the keystone species of the ecosystem of the Southern Ocean, being an important food organism for whales, seals, leopard seals, fur seals, squid, icefish, and many bird species, such as penguins and albatrosses. Some species of marine animals exist and rely, directly or indirectly, on phytoplankton. Antarctic sea life includes penguins, blue whales, orcas, colossal squids and fur seals. The Antarctic fur seal was very heavily hunted in the 18th and 19th centuries for its pelt by seal hunters from the United States and the United Kingdom. Leopard seals are apex predators in the Antarctic ecosystem and migrate across the Southern Ocean in search of food.

There are approximately 40 bird species that breed on or close to Antarctica, including species of petrels, penguins, cormorants, and gulls. Various other bird species visit the ocean around Antarctica, including some that normally reside in the Arctic. The emperor penguin is the only penguin that breeds during the winter in Antarctica; it and the Adélie penguin breed farther south than any other penguin.

A Census of Marine Life by some 500 researchers during the International Polar Year was released in 2010. The research found that more than 235 marine organisms live in both polar regions, having bridged the gap of 12,000 km (7,456 mi). Large animals such as some cetaceans and birds make the round trip annually. Smaller forms of life, such as sea cucumbers and free-swimming snails, are also found in both polar oceans. Factors that may aid in their distribution include temperature differences between the deep ocean at the poles and the equator of no more than 5 °C (9 °F) and the major current systems or marine conveyor belts which are able to transport eggs and larva.

Fungi

About 1,150 species of fungi have been recorded in the Antarctic region, of which about 750 are non-lichen-forming. Some of the species, having evolved under extreme conditions, have colonised structural cavities within porous rocks and have contributed to shaping the rock formations of the McMurdo Dry Valleys and surrounding mountain ridges.

The simplified morphology of such fungi, along with their similar biological structures, metabolism systems capable of remaining active at very low temperatures, and reduced life cycles, make them well suited to such environments. Their thick-walled and strongly melanised cells make them resistant to UV radiation. An Antarctic endemic species, the crust-like lichen Buellia frigida, has been used as a model organism in astrobiology research.

The same features can be observed in algae and cyanobacteria, suggesting that they are adaptations to the conditions prevailing in Antarctica. This has led to speculation that life on Mars might have been similar to Antarctic fungi, such as Cryomyces antarcticus and Cryomyces minteri. Some of the species of fungi, which are apparently endemic to Antarctica, live in bird dung, and have evolved so they can grow inside extremely cold dung, but can also pass through the intestines of warm-blooded animals.

Plants

Throughout its history, Antarctica has seen a wide variety of plant life. In the Cretaceous, it was dominated by a fern-conifer ecosystem, which changed into a temperate rainforest by the end of that period. During the colder Neogene (17–2.5 Ma), a tundra ecosystem replaced the rainforests. The climate of present-day Antarctica does not allow extensive vegetation to form. A combination of freezing temperatures, poor soil quality, and a lack of moisture and sunlight inhibit plant growth, causing low species diversity and limited distribution. The flora largely consists of bryophytes (25 species of liverworts and 100 species of mosses). There are three species of flowering plants, all of which are found in the Antarctic Peninsula: Deschampsia antarctica (Antarctic hair grass), Colobanthus quitensis (Antarctic pearlwort) and the non-native Poa annua (annual bluegrass).

Other organisms

Of the 700 species of algae in Antarctica, around half are marine phytoplankton. Multicoloured snow algae are especially abundant in the coastal regions during the summer. Even sea ice can harbour unique ecological communities, as it expels all salt from the water when it freezes, which accumulates into pockets of brine that also harbour dormant microorganisms. When the ice begins to melt, brine pockets expand and can combine to form brine channels, and the algae inside the pockets can reawaken and thrive until the next freeze. Bacteria have also been found as deep as 800 m (0.50 mi) under the ice. It is thought to be likely that there exists a native bacterial community within the subterranean water body of Lake Vostok. The existence of life there is thought to strengthen the argument for the possibility of life on Jupiter's moon Europa, which may have water beneath its water-ice crust. There exists a community of extremophile bacteria in the highly alkaline waters of Lake Untersee. The prevalence of highly resilient creatures in such inhospitable areas could further bolster the argument for extraterrestrial life in cold, methane-rich environments.

Conservation and environmental protection

The first international agreement to protect Antarctica's biodiversity was adopted in 1964. The overfishing of krill (an animal that plays a large role in the Antarctic ecosystem) led officials to enact regulations on fishing. The Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, an international treaty that came into force in 1980, regulates fisheries, aiming to preserve ecological relationships. Despite these regulations, illegal fishing—particularly of the highly prized Patagonian toothfish which is marketed as Chilean sea bass in the U.S.—remains a problem.

In analogy to the 1980 treaty on sustainable fishing, countries led by New Zealand and the United States negotiated a treaty on mining. This Convention on the Regulation of Antarctic Mineral Resource Activities was adopted in 1988. After a strong campaign from environmental organisations, first Australia and then France decided not to ratify the treaty. Instead, countries adopted the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (the Madrid Protocol), which entered into force in 1998. The Madrid Protocol bans all mining, designating the continent as a "natural reserve devoted to peace and science".

The pressure group Greenpeace established a base on Ross Island from 1987 to 1992 as part of its attempt to establish the continent as a World Park. The Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary was established in 1994 by the International Whaling Commission. It covers 50 million km2 (19 million sq mi) and completely surrounds the Antarctic continent. All commercial whaling is banned in the zone, though Japan has continued to hunt whales in the area, ostensibly for research purposes.

Despite these protections, the biodiversity in Antarctica is still at risk from human activities. Specially protected areas cover less than 2% of the area and provide better protection for animals with popular appeal than for less visible animals. There are more terrestrial protected areas than marine protected areas. Ecosystems are impacted by local and global threats, notably pollution, the invasion of non-native species, and the various effects of climate change.

History of exploration

Early world maps, like the 1513 Piri Reis map, feature the hypothetical continent Terra Australis. Much larger than and unrelated to Antarctica, Terra Australis was a landmass that classical scholars presumed necessary to balance the known lands in the northern hemisphere.

Captain James Cook's ships, HMS Resolution and Adventure, crossed the Antarctic Circle on 17 January 1773, in December 1773, and again in January 1774. Cook came within about 120 km (75 mi) of the Antarctic coast before retreating in the face of field ice in January 1773. In 1775, he called the existence of a polar continent "probable", and in another copy of his journal he wrote: "[I] firmly believe it and it's more than probable that we have seen a part of it".

19th century

Sealers were among the earliest to go closer to the Antarctic landmass, perhaps in the earlier part of the 19th century. The oldest known human remains in the Antarctic region was a skull, dated from 1819 to 1825, that belonged to a young woman on Yamana Beach at the South Shetland Islands. The woman, who was likely to have been part of a sealing expedition, was found in 1985.

The first person to see Antarctica or its ice shelf was long thought to have been the British sailor Edward Bransfield, a captain in the Royal Navy, who discovered the tip of the Antarctic peninsula on 30 January 1820. However, a captain in the Imperial Russian Navy, Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen, recorded seeing an ice shelf on 27 January. The American sealer Nathaniel Palmer, whose sealing ship was in the region at this time, may also have been the first to sight the Antarctic Peninsula.

The First Russian Antarctic Expedition, led by Bellingshausen and Mikhail Lazarev on the 985-ton sloop-of-war Vostok and the 530-ton support vessel Mirny, reached a point within 32 km (20 mi) of Queen Maud Land and recorded sighting an ice shelf at 69°21′28″S 2°14′50″W / 69.35778°S 2.24722°W, on 27 January 1820. The sighting happened three days before Bransfield sighted the land of the Trinity Peninsula of Antarctica, as opposed to the ice of an ice shelf, and 10 months before Palmer did so in November 1820. The first documented landing on Antarctica was by the English-born American sealer John Davis, apparently at Hughes Bay on 7 February 1821, although some historians dispute this claim, as there is no evidence Davis landed on the Antarctic continent rather than an offshore island.

On 22 January 1840, two days after the discovery of the coast west of the Balleny Islands, some members of the crew of the 1837–1840 expedition of the French explorer Jules Dumont d'Urville disembarked on the Dumoulin Islands, off the coast of Adélie Land, where they took some mineral, algae, and animal samples, erected the French flag, and claimed French sovereignty over the territory. The American captain Charles Wilkes led an expedition in 1838–1839 and was the first to claim he had discovered the continent. The British naval officer James Clark Ross failed to realise that what he referred to as "the various patches of land recently discovered by the American, French and English navigators on the verge of the Antarctic Circle" were connected to form a single continent. The American explorer Mercator Cooper landed on East Antarctica on 26 January 1853.

The first confirmed landing on the continental mass of Antarctica occurred in 1895 when the Norwegian-Swedish whaling ship Antarctic reached Cape Adare.

20th century

During the Nimrod Expedition led by the British explorer Ernest Shackleton in 1907, parties led by Edgeworth David became the first to climb Mount Erebus and to reach the south magnetic pole. Douglas Mawson, who assumed the leadership of the Magnetic Pole party on their perilous return, retired in 1931. Between December 1908 and February 1909, Shackleton and three members of his expedition became the first humans to traverse the Ross Ice Shelf, the first to cross the Transantarctic Mountains (via the Beardmore Glacier), and the first to set foot on the south Polar Plateau. On 14 December 1911, an expedition led by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen from the ship Fram became the first to reach the geographic South Pole, using a route from the Bay of Whales and up the Axel Heiberg Glacier. One month later, the doomed Terra Nova Expedition reached the pole.

The American explorer Richard E. Byrd led four expeditions to Antarctica during the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, using the first mechanised tractors. His expeditions conducted extensive geographical and scientific research, and he is credited with surveying a larger region of the continent than any other explorer. In 1937, Ingrid Christensen became the first woman to step onto the Antarctic mainland. Caroline Mikkelsen had landed on an island of Antarctica, earlier in 1935.

The South Pole was next reached on 31 October 1956, when a U.S. Navy group led by Rear Admiral George J. Dufek successfully landed an aircraft there. Six women were flown to the South Pole as a publicity stunt in 1969. In the summer of 1996–1997, Norwegian explorer Børge Ousland became the first person to cross Antarctica alone from coast to coast, helped by a kite on parts of the journey. Ousland holds the record for the fastest unsupported journey to the South Pole, taking 34 days.

Demographics

The first semi-permanent inhabitants of regions near Antarctica (areas situated south of the Antarctic Convergence) were British and American sealers who used to spend a year or more on South Georgia, from 1786 onward. During the whaling era, which lasted until 1966, the population of the island varied from over 1,000 in the summer (over 2,000 in some years) to some 200 in the winter. Most of the whalers were Norwegian, with an increasing proportion from Britain.

Antarctica's population consists mostly of the staff of research stations in Antarctica (which are continuously maintained despite the population decline in the winter), although there are 2 all-civilian bases in Antarctica: the Esperanza Base and the Villa Las Estrellas base. The number of people conducting and supporting scientific research and other work on the continent and its nearby islands varies from about 1,200 in winter to about 4,800 in the summer, with an additional 136 people in the winter to 266 people in the summer from the 2 civilian bases (as of 2017). Some of the research stations are staffed year-round, the winter-over personnel typically arriving from their home countries for a one-year assignment. The Russian Orthodox Holy Trinity Church at the Bellingshausen Station on King George Island opened in 2004; it is staffed year-round by one or two priests, who are similarly rotated every year.

The first child born in the southern polar region was a Norwegian girl, Solveig Gunbjørg Jacobsen, born in Grytviken on 8 October 1913. Emilio Marcos Palma was the first person born south of the 60th parallel south and the first to be born on the Antarctic mainland at the Esperanza Base of the Argentine Army, on 7 January 1978.

The Antarctic Treaty prohibits any military activity in Antarctica, including the establishment of military bases and fortifications, military manoeuvres, and weapons testing. Military personnel or equipment are permitted only for scientific research or other peaceful purposes. Operation 90 by the Argentine military in 1965 was conducted to strengthen Argentina's claim in Antarctica.

Antarctic English, a distinct variety of the English language, has been found to be spoken by people living on Antarctica and the subantarctic islands.

Politics

Antarctica's status is regulated by the 1959 Antarctic Treaty and other related agreements, collectively called the Antarctic Treaty System. Antarctica is defined as all land and ice shelves south of 60° S for the purposes of the Treaty System. The treaty was signed by twelve countries, including the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, Argentina, Chile, Australia, and the United States. Since 1959, a further 42 countries have acceded to the treaty. Countries can participate in decision-making if they can demonstrate that they do significant research on Antarctica; as of 2022[update], 29 countries have this 'consultative status'. Decisions are based on consensus, instead of a vote. The treaty set aside Antarctica as a scientific preserve and established freedom of scientific investigation and environmental protection.

Territorial claims

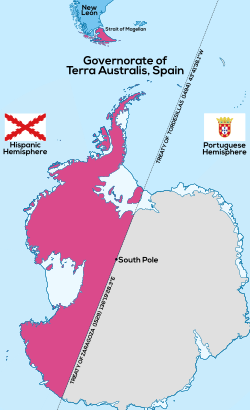

In 1539, the King of Spain, Charles V, created the Governorate of Terra Australis, which encompassed lands south of the Strait of Magellan and thus theoretically Antarctica, the existence of which was only hypothesized at the time, granting this Governorate to Pedro Sancho de la Hoz, who in 1540 transferred the title to the conquistador Pedro de Valdivia. Spain claimed all the territories to the south of the Strait of Magellan until the South Pole, with eastern and western borders to these claims specified in the Treaty of Tordesillas and Zaragoza respectively. In 1555 the claim was incorporated to Chile.

In the present, sovereignty over regions of Antarctica is claimed by seven different countries. While a few of these countries have mutually recognised each other's claims, the validity of the claims is not recognised universally. New claims on Antarctica have been suspended since 1959, although in 2015, Norway formally defined Queen Maud Land as including the unclaimed area between it and the South Pole.

The Argentine, British, and Chilean claims overlap and have caused friction. In 2012, after the British Foreign & Commonwealth Office designated a previously unnamed area Queen Elizabeth Land in tribute to Queen Elizabeth II's Diamond Jubilee, the Argentine government protested against the claim. The UK passed some of the areas it claimed to Australia and New Zealand after they achieved independence. The claims by Britain, Australia, New Zealand, France, and Norway do not overlap and are recognised by each other. Other member nations of the Antarctic Treaty do not recognise any claim, yet have shown some form of territorial interest in the past.

Brazil has a designated "zone of interest" that is not considered an actual claim.

Brazil has a designated "zone of interest" that is not considered an actual claim. Peru formally reserved its right to make a claim.

Peru formally reserved its right to make a claim. Russia inherited the Soviet Union's right to claim territory under the original Antarctic Treaty.

Russia inherited the Soviet Union's right to claim territory under the original Antarctic Treaty. South Africa formally reserved its right to make a claim.

South Africa formally reserved its right to make a claim. The United States reserved its right to make a claim in the original Antarctic Treaty.

The United States reserved its right to make a claim in the original Antarctic Treaty.

Economy and tourism

Deposits of coal, hydrocarbons, iron ore, platinum, copper, chromium, nickel, gold, and other minerals have been found in Antarctica, but not in large enough quantities to extract. The Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, which came into effect in 1998 and is due to be reviewed in 2048, restricts the exploitation of Antarctic resources, including minerals.

Tourists have been visiting Antarctica since 1957. Tourism is subject to the provisions of the Antarctic Treaty and Environmental Protocol; the self-regulatory body for the industry is the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators. Tourists arrive by small or medium ship at specific scenic locations with accessible concentrations of iconic wildlife. Over 74,000 tourists visited the region during the 2019–2020 season, of which 18,500 travelled on cruise ships but did not leave them to explore on land. The numbers of tourists fell rapidly after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some nature conservation groups have expressed concern over the potential adverse effects caused by the influx of visitors and have called for limits on the size of visiting cruise ships and a tourism quota. The primary response by Antarctic Treaty parties has been to develop guidelines that set landing limits and closed or restricted zones on the more frequently visited sites.

Tourism in Antarctica is, in part, ecologically focused with expeditions being offered for bird watching tours due to the high numbers of Adélie, King, and Gentoo penguins – among other species. One site in particular – McDonald Beach – is known to be a high-traffic area for tourists watching the Adélie penguins who number more than 40,000.

Overland sightseeing flights operated out of Australia and New Zealand until the Mount Erebus disaster in 1979, when an Air New Zealand plane crashed into Mount Erebus, killing all of the 257 people on board. Qantas resumed commercial overflights to Antarctica from Australia in the mid-1990s. There are many airports in Antarctica.

Research

In 2017, there were more than 4,400 scientists undertaking research in Antarctica, a number that fell to just over 1,100 in the winter. There are over 70 permanent and seasonal research stations on the continent; the largest, United States' McMurdo Station, is capable of housing more than 1,000 people. The British Antarctic Survey has five major research stations on Antarctica, one of which is completely portable. The Belgian Princess Elisabeth station is one of the most modern stations and the first to be carbon-neutral. Argentina, Australia, Chile, and Russia also have a large scientific presence on Antarctica.

Geologists primarily study plate tectonics, meteorites, and the breakup of Gondwana. Glaciologists study the history and dynamics of floating ice, seasonal snow, glaciers, and ice sheets. Biologists, in addition to researching wildlife, are interested in how low temperatures and the presence of humans affect adaptation and survival strategies in organisms. Biomedical scientists have made discoveries concerning the spreading of viruses and the body's response to extreme seasonal temperatures.

The high elevation of the interior, the low temperatures, and the length of polar nights during the winter months all allow for better astronomical observations at Antarctica than anywhere else on Earth.

The view of space from Earth is improved by a thinner atmosphere at higher elevations and a lack of water vapour in the atmosphere caused by freezing temperatures. Astrophysicists at the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station study cosmic microwave background radiation and neutrinos from space.

The largest neutrino detector in the world, the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, is at the Amundsen-Scott Station. It consists of around 5,500 digital optical modules, some of which reach a depth of 2,450 m (8,040 ft), that are held in 1 km3 (0.24 cu mi) of ice. Scientists also observed higher radiation dose rates around the coast of Antarctica compared with the global average: this is attributed to cosmic rays going through the thinner atmosphere compared to equatorial latitudes.

Antarctica provides a unique environment for the study of meteorites: the dry polar desert preserves them well, and meteorites older than a million years have been found. They are relatively easy to find, as the dark stone meteorites stand out in a landscape of ice and snow, and the flow of ice accumulates them in certain areas.

The Adelie Land meteorite, discovered in 1912, was the first to be found. Meteorites contain clues about the composition of the Solar System and its early development. Most meteorites come from asteroids, but a few meteorites found in Antarctica came from the Moon and Mars.

Major scientific organizations in Antarctica have released strategy and action plans focused on advancing national interests and objectives in Antarctica, supporting cutting-edge research to understand the interactions between the Antarctic region and climate systems. The British Antarctic Survey (BAS) released a 10-year (2023–2033) strategy report to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to focus on creating sustainable living on Earth. Environmental sustainability is named as one of the top focus areas by the BAS strategy, highlighting the main challenge and priority to embed environmental sustainability into everything.

In 2022, the Australian Antarctic Program (AAP) released a new Strategy and 20-year Action Plan (2022–2036) to modernize its Antarctic program. The global climate system was highlighted as one of the main priorities that will be supported and studied through the AAP Strategy Plan. It emphasizes the importance of understanding the vital role of Antarctica and the Southern Ocean in climate and weather to improve current knowledge and inform management responses.

In 2021, the United States Antarctic Program (USAP) released a Midterm Assessment on the 2015 Strategic Vision for Antarctic and Southern Ocean Research, stressing the prominent role of the Southern Ocean in the global carbon cycle and sea level rise. The USAP outlines the Changing Antarctic Ice Sheets Initiative as a top priority to enhance understanding of why ice sheets are changing now, and how they will change in the future.

Antarctic ice sheets are a central focus of contemporary climate research due to urgent questions about their stability and reaction to global warming. Satellite technology enables researchers to study the ice sheets both through on-site fieldwork and remote sensing, facilitating detailed analyses of ice dynamics to predict future changes in a warming world.

The INStabilities & Thresholds in ANTarctica (INSTANT) Scientific Research Programme proposes three research themes, investigating the complex interactions between the atmosphere, ocean, and solid Earth in Antarctica. Its aims include improving the understanding and predictions of these processes to aid decision makers in risk assessment, management, and mitigation related to Antarctic climate change.

The Australian-led ICECAP project utilized advanced aerogeophysical techniques to map deep subglacial basins and channels that connect the ice sheet to the ocean. This mapping improves predictions of ice sheet stability, the impacts of climate change on the ice sheets, and their potential contributions to global sea level rise.

Culture

Music and film

The southernmost music festival in the world, Icestock, has been held at McMurdo Station since 1989. The organizers, performers, and attendees of Icestock are all personnel working at McMurdo or nearby Scott Base. The Antarctic Film Festival is held annually between bases, with 48 stations registered to participate as of 2022. The festival is designed for short films of 5 minutes or less.

In 2011, Australian classical harpist Alice Giles became the first professional musician to perform in Antarctica. The first full-length fictional film to be shot in Antarctica was South of Sanity, a 2012 low budget British horror film. An upcoming film directed by Nick Cassavetes and starring Anthony Hopkins, Bruno Penguin and the Staten Island Princess, will be the first major Hollywood production to shoot in Antarctica.

Sport

Sporting events held on Antarctica include the Antarctic Ice Marathon & 100k ultra race, Antarctica Marathon and Antarctica Cup Yacht Race. Association football has been played since the early twentieth century, with teams representing bases or visiting ships.

Holidays

There are two principal holidays celebrated across Antarctica: Midwinter Day on the day of the southern winter solstice (June 20 or 21) and Antarctica Day on December 1, which commemorates the signing of the Antarctic Treaty in 1959.

See also

Notes

References

Bibliography

Further reading

- De Pomereu, Jean; and McCahey, Daniella. Antarctica: A History in 100 Objects (Conway, 2022) online book review

- Kleinschmidt, Georg (2021). The geology of the Antarctic continent. Stuttgart: Bornträger Science Publisher. ISBN 978-3-443-11034-5.

- Lucas, Mike (1996). Antarctica. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85368-743-3.

- Mardon, Austin Albert; Mardon, Catherine (2009). The use of geographic remote sensing, mapping and aerial photography to aid in the recovery of blue ice surficial meteorites in Antarctica. Edmonton: Golden Meteorite Press. ISBN 978-18974-7-235-4 – via Internet Archive.

- Stewart, John (2011). Antarctica: An Encyclopedia. Jefferson, N.C. and London: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3590-6.

- Ivanov, Lyubomir; Ivanova, Nusha (2022). The World of Antarctica. Generis Publishing. 241 pp.ISBN 979-8-88676-403-1

External links

- Official website of the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat (de facto government)

- High resolution map (2022) – Reference Elevation Model of Antarctica (REMA)

- Antarctica. on In Our Time at the BBC

- British Antarctic Survey (BAS)

- U.S. Antarctic Program Portal