Carl von Ossietzky

Carl von Ossietzky (

German pronunciation: [ˈkaʁl fɔn ʔɔˈsi̯ɛtskiː] ⓘ; 3 October 1889 – 4 May 1938) was a German journalist and pacifist. He was the recipient of the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize for his work in exposing the clandestine German rearmament.As editor-in-chief of the magazine Die Weltbühne, Ossietzky published a series of exposés in the late 1920s, detailing Germany's violation of the Treaty of Versailles by rebuilding an air force (the predecessor of the Luftwaffe) and training pilots in the Soviet Union. He was convicted of treason and espionage in 1931 and sentenced to eighteen months in prison but was granted amnesty in December 1932.

Ossietzky continued to be a vocal critic against German militarism after the Nazis' rise to power. Following the 1933 Reichstag fire, Ossietzky was again arrested and sent to the Esterwegen concentration camp near Oldenburg. His brutal torture after his arrest was attested by International Red Cross. In 1936, he was awarded the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize, but was forbidden from travelling to Norway to accept the prize. After enduring years of mistreatment in Nazi concentration camps, Ossietzky died of tuberculosis in 1938 in a Berlin hospital after more than five years of imprisonment.

Early life

Ossietzky was born in Hamburg, the son of Carl Ignatius von Ossietzky (1848–1891), a Protestant from Upper Silesia, and Rosalie (née Pratzka), a devout Catholic who wanted her son to enter Holy Orders and become a priest or monk. His father worked as a stenographer in the office of a lawyer, and of senator Max Predöhl, but died when Ossietzky was two years old. Ossietzky was baptized as a Roman Catholic in Hamburg on 10 November 1889 and confirmed in the Lutheran Hauptkirche St Michaelis on 23 March 1904.

The von in Ossietzky's name, which would generally suggest noble ancestry, is of unknown origin. Ossietzky himself explained, perhaps half in jest, that it derived from an ancestor's service in a Polish lancer cavalry regiment as the Elector of Brandenburg was unable to pay his two regiments of lancers at one point due to an empty war chest, so he instead conferred nobility upon the entirety of the two regiments.

Despite his failure to finish Realschule (a form of German secondary school), Ossietzky succeeded in embarking on a career in journalism, with the topics of his articles ranging from theatre criticism to feminism and the problems of early motorisation. He later said that his opposition to German militarism during the final years of the German Empire under Wilhelm II led him as early as 1913 to become a pacifist.

That year, he married Maud Lichfield-Woods, a Mancunian suffragette, born to British colonial officer and the great-granddaughter of an Indian princess in Hyderabad. They had one daughter, Rosalinda. During World War I, Ossietzky was drafted much against his will into the Army and his experiences during the war – where he was appalled by the carnage – confirmed him in his pacifism. During the Weimar Republic (1919–1933), his political commentaries gained him a reputation as a fervent supporter of democracy and a pluralistic society.

Discovery of illegal German rearmament

In 1921, the German military founded the Arbeitskommandos (work squads) built up by Major Bruno Ernst Buchrucker. Officially labour groups intended to assist with civilian projects, in reality the members were soldiers secretly trained by the Reichswehr in order to exceed the limits on troop strength set by the Treaty of Versailles.

The Black Reichswehr took its orders from a group in the German Army led by Fedor von Bock, Kurt von Schleicher, Eugen Ott and Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord. The Black Reichswehr became infamous for using Feme murders to punish "traitors" who, for example, revealed the locations of weapons' stockpiles or names of members. Secret "trials" were conducted of which the victims were unaware, and after finding the accused guilty they would send out a man to execute the "court's" sentence of death. During the trials of some of those charged with the murders, prosecutors alleged that the killings were ordered by the officers from Bock's group. Regarding the Feme murders, Ossietzky wrote:

Reflecting his pacifism, Ossietzky became secretary of the German Peace Society (German: Deutsche Friedensgesellschaft) in 1919.

"Homeless left"

In the 1920s, Ossietzky became one of the leaders of the "homeless left", centered on the newspaper Die Weltbühne which rejected Communism, but found the Social Democrats too inclined to compromise with the old order.

Ossietzky often complained that the men who staffed the bureaucracy, the judiciary and the military under the Kaiser were the same men serving the Weimar Republic, something that was a major concern for him as he frequently warned that these men had no commitment to democracy, and would turn against the republic at the first chance.

In this regard, Ossietzky at Die Weltbühne helped to publish a statistical study in 1923, showing that German judges were inclined to impose extremely harsh sentences on those who broke laws in the name of the left while imposing very lenient sentences on those who committed much violence in the name of the right. He often drew a contrast between the fate of Social Democrat Felix Fechenbach who was imprisoned after a questionable trial for publishing secret documents showing that the German Empire was responsible for World War I and that of the Navy captain Hermann Ehrhardt of the Freikorps whose men occupied Berlin during the Kapp Putsch, killed several hundred civilians and was never tried for his actions. At the same time, Ossietzky was often critical of those republicans who claimed to believe in democracy without actually knowing what democracy meant.

Ossietzky was especially critical of the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold (Reich Banner Black-Red-Gold), the paramilitary group set up by the Social Democrats to defend democracy. Ossietzky wrote in 1924:

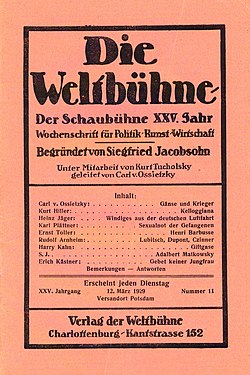

In 1927, Ossietzky succeeded Kurt Tucholsky as editor-in-chief of the periodical Die Weltbühne. In 1932, he supported Ernst Thälmann's candidacy for the German presidency, though still a critic of the actual policy of the German Communist Party and the Soviet Union.

Abteilung M affair

On 12 March 1929 Die Weltbühne published an article by Walter Kreiser, one of its writers: an exposé of the training of a special air unit of the Reichswehr, referred to as Abteilung M (Section M), which was secretly training in Germany and in Soviet Russia, in violation of Germany's agreements under the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. Kreiser and Ossietzky, the paper's editor, were questioned by a magistrate of the Supreme Court about the article later that year and were finally indicted in early 1931 for "treason and espionage", the assertion being that they had drawn international attention to state affairs which the state had purposefully attempted to keep secret. The arrests were widely seen at the time as an effort to silence Die Weltbühne, which had been a vocal critic of the Reichswehr's policies and secret expansion.[need quotation to verify]

Counsel for the defendants pointed out that the information they had published was true, and – more to the point – that the budgeting for Abteilung M had actually been cited in reports by the Reichstag's budgeting commission. The prosecution successfully countered that Kreiser (and Ossietzky as his editor) should have known that the reorganization was a state secret when he questioned the Ministry of Defense on the subject of Abteilung M and the ministry refused to comment on it. Kreiser and Ossietzky were convicted and sentenced by the Reichsgericht on 23 November 1931 to eighteen months in prison. Kreiser fled Germany, but Ossietzky remained and was imprisoned, being released at the end of 1932 on the occasion of the Christmas amnesty.

Arrest by the Nazis

Ossietzky continued to be a constant warning voice against militarism and Nazism. In 1932, he published an article in which he stated:

In the same essay, Ossietzky wrote:

Finally, Ossietzky warned: "Today there is a strong smell of blood in the air. Literary anti-Semitism forges the moral weapon for murder. Sturdy and honest lads will take care of the rest".

Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor in January 1933, the Nazi dictatorship began soon after in late March with the Enabling Act of 1933, but even then Ossietzky was one of a very small group of public figures who continued to speak out against the Nazi Party. On 28 February 1933, after the Reichstag fire, he was arrested and held in so-called protective custody in Spandau prison. Wilhelm von Sternburg, one of Ossietzky's biographers, surmises that if Ossietzky had had a few more days, he would surely have joined the vast majority of writers who fled the country. In short, Ossietzky underestimated the speed with which the Nazis would go about ridding the country of unwanted political opponents. He was detained afterwards at the Esterwegen concentration camp near Oldenburg, among other camps. Throughout his time in the concentration camps, Ossietzky was mercilessly mistreated by the guards while being deprived of food. In November 1935, when a representative of the International Red Cross visited Ossietzky, he reported that he saw "a trembling, deadly pale something, a creature that appeared to be without feeling, one eye swollen, teeth knocked out, dragging a broken, badly healed leg . . . a human being who had reached the uttermost limits of what could be borne".

1935 Nobel Peace Prize

Ossietzky's international rise to fame began in 1936 when, already suffering from serious tuberculosis, he was awarded the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize. The government had been unable to prevent this but refused to release him to travel to Oslo to receive the prize. In an act of civil disobedience, after Hermann Göring prompted him to decline the prize, Ossietzky issued a note from the hospital saying that he disagreed with the authorities who had stated that by accepting the prize he would cast himself outside the deutsche Volksgemeinschaft (community of German people):

The award was extremely controversial, prompting two members of the prize committee to resign because they held or had held positions in the Norwegian government. King Haakon VII of Norway, who had been present at other award ceremonies, stayed away from the ceremony.

The award divided public opinion and was generally condemned by conservative forces. The leading conservative Norwegian newspaper Aftenposten argued in an editorial that Ossietzky was a criminal who had attacked his country "with the use of methods that violated the law long before Hitler came into power" and that "lasting peace between peoples and nations can only be achieved by respecting the existing laws".

Ossietzky's Nobel Prize was not allowed to be mentioned in the German press and a government decree forbade German citizens from accepting future Nobel Prizes.

Death

In May 1936, Ossietzky was sent to the Westend hospital in Berlin-Charlottenburg because of his tuberculosis, but under Gestapo surveillance. On 4 May 1938, he died in the Nordend hospital in Berlin-Pankow, still in police custody, of tuberculosis and from the after-effects of the abuse he suffered in the concentration camps.

Legacy

Supporters of convicted Nobel Prize-winning Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo compared him to Ossietzky, both being prevented by the authorities from accepting their awards and both having died while in custody. The International League for Human Rights (Berlin) awards an annual Carl von Ossietzky Medal "to honor citizens or initiatives that promote basic human rights".

In 1963, East German television produced the film Carl von Ossietzky about Ossietzky's life, starring Hans-Peter Minetti in the title role.

In 1991, the University of Oldenburg was renamed Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg in his honor. Ossietzky's daughter Rosalinde von Ossietzky-Palm took part in the formal ceremony, accompanied by then Prime Minister of Lower Saxony Gerhard Schröder.

In 1992, Ossietzky's 1931 conviction was upheld by Germany's Bundesgerichtshof (Federal Court of Justice), applying the law as it stood in 1931.

See also

References

Further reading

- Brumlik, Micha. "Resistance. Carl von Ossietzky, Albert Leo Schlageter, and Mahatma Gandhi". Resistance 2017. 17–30. online

- Buse, Dieter K. and Juergen C. Doerr, eds. Modern Germany: An Encyclopedia of History, People, and Culture, 1871–1990 (2 vol. Garland, 1998) 2:734.

- Von Ossietzky, Carl. The Stolen Republic: Selected Writings of Carl Von Ossietzky (Lawrence and Wishart, 1971).

- Tres, Richard: "The Man without a Party: The Trials of Carl von Ossietzky". Beacon Publishing Group, 2019,ISBN 978-1-949472-88-2

In German

- Ossietzky, Carl von (1988). Stefan Berkholz (ed.). 227 Tage im Gefängnis. Briefe, Texte, Dokumente (in German). Darmstadt: Luchterhand Literatur Verlag.

- Carl von Ossietzky, Peter Jörg Becker; Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg. 1975 Die theologischen Handschriften der Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg: Die Foliohandschriften, Volume 1. Dr. Ernst Hauswedell & Co. (in German).

- Maud von Ossietzky: Maud von Ossietzky erzählt: Ein Lebensbild. Berlin 1966 (in German).

- Boldt, Werner: Carl von Ossietzky: Vorkämpfer der Demokratie. Berlin 2013,ISBN 978-3-944545-00-4.

- Kurt Buck: Carl von Ossietzky im Konzentrationslager. In: DIZ-Nachrichten. Aktionskomitee für ein Dokumentations- und Informationszentrum Emslandlager e.V., Papenburg 2009, Nr. 29, S. 21–27 : Ill (in German).

- Gerhard Kraiker, Dirk Grathoff, eds: Carl von Ossietzky und die politische Kultur der Weimarer Republik. Symposium zum 100. Geburtstag. Schriftenreihe des Fritz Küster-Archivs. Oldenburg 1991 (in German).

- Helmut Reinhardt (Hrsg.): Nachdenken über Ossietzky. Aufsätze und Graphik. Verlag der Weltbühne von Ossietzky, Berlin 1989,ISBN 3-86020-011-9 (in German).

- Christoph Schottes: Die Friedensnobelpreiskampagne für Carl von Ossietzky in Schweden. Oldenburg 1997,ISBN 3-8142-0587-1 (in German). Buch als PDF

- Richard von Soldenhoff, ed: Carl von Ossietzky 1889–1938. Ein Lebensbild. (Bildbiografie). Weinheim 1988,ISBN 3-88679-173-4 (in German).

- Wilhelm von Sternburg: "Es ist eine unheimliche Stimmung in Deutschland": Carl von Ossietzky und seine Zeit. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 1996,ISBN 3-351-02451-7 (in German).

- Elke Suhr: Zwei Wege, ein Ziel – Tucholsky, Ossietzky und Die Weltbühne. Weisman, München 1986,ISBN 3-88897-026-1 (in German).

- Elke Suhr: Carl von Ossietzky. Eine Biographie. Kiepenheuer und Witsch, Köln 1988,ISBN 3-462-01885-X (in German).

- Frithjof Trapp, Knut Bergmann, Bettina Herre: Carl von Ossietzky und das politische Exil. Die Arbeit des „Freundeskreises Carl von Ossietzky" in den Jahren 1933–1936. Hamburg 1988 (in German).

- Berndt W. Wessling: Carl von Ossietzky, Märtyrer für den Frieden. München 1989,ISBN 3-926901-17-9 (in German).

External links

- Carl von Ossietzky on Nobelprize.org

- 1935 Nobel Peace Prize presentation speech

- Works by or about Carl von Ossietzky at the Internet Archive

- Works by Carl von Ossietzky at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Newspaper clippings about Carl von Ossietzky in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW