Cranchiidae

The family Cranchiidae comprises the approximately 60 species of glass squid, also known as cockatoo squid, bathyscaphoid squid, cranch squid, or simply cranchiids. The common name "glass squid" derives from the transparent bodies of most species. Cranchiid squid occur in surface and midwater depths of open oceans around the world. Cranchiid squid spend much of their lives in partially sunlit shallow waters, where their transparency provides camouflage.[dubious – discuss]

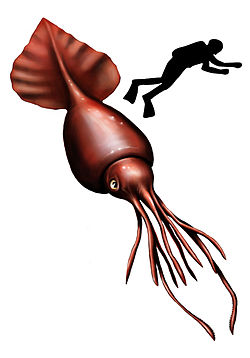

Like most squid, the juveniles of cranchiid squid live in surface waters, descending to deeper waters as they mature. Some species live over 2 km below sea level. The body shape of many species changes drastically between growth stages, and many young examples could be confused for different species altogether. The family ranges in mantle length from 10 cm (3.9 in) to over 3 m (9.8 ft), in the case of the colossal squid, which is the largest invertebrate alive.

The type genus of the family, Cranchia, is named for English naturalist John Cranch. Cranchiid squid are of no interest to commercial fisheries.

Description

The family is characterised by an enlarged mantle and short arms that bear two rows of suckers or hooks, with the third pair of arms often enlarged. Eye morphology varies widely, ranging from large and circular to telescopic and stalked. Recent studies have revealed that certain cranchiid squids, such as Galiteuthis glacialis, possess photophores—light-producing organs—on their eyes. These photophores emit bioluminescence that matches the intensity of downwelling sunlight, effectively masking the squid's silhouette from predators below. This counter-illumination strategy is a sophisticated form of camouflage in the mesopelagic zone. The photophores consist of laminated, fiber-like cells with semi-coaxial protein-dense layers surrounding axial cytoplasm, enabling precise control over light emission. The only organ that is typically visible through the transparent tissues is a cigar-shaped digestive gland, a cephalopod analogue of the liver; this organ is usually held in a vertical position to reduce its silhouette. Many species are bioluminescent and may possess light organs on the lower tip of their digestive gland and on the undersides of their eyes, used to cancel their shadows and evade predators. Cranchiids have lower activity levels and metabolic rates than other families of squid, being more sedentary.

A large, fluid-filled coelomic cavity containing ammonia solution is used to aid buoyancy. This buoyancy system is unique to the family and is the source of their common name "bathyscaphoid squid", after their resemblance to a bathyscaphe. This system appears to develop further as cranchiids mature and move from surface waters to bathypelagic zones. By consolidating ammonia in one compartment, they minimize energy costs associated with staying neutrally buoyant. Observations suggest that juveniles maintain lower ammonium levels in the sac, possibly reflecting foraging in shallower habitats, whereas adults exhibit higher concentrations for stable flotation in deeper depths.

Diet

Cranchiids occupy a variety of trophic levels, with some species relying heavily on mesopelagic crustaceans such as copepods and small fishes; cranchiids as a whole may prey on a broad variety of species. Recent research using fatty acid and stable isotope analyses has shown that smaller cranchiids in the Benguela Upwelling System feed at mid to lower trophic levels, whereas larger, more muscular squid such as Todarodes and Abraliopsis occupy higher trophic positions; the ecological niche of cranchiids has even been compared to those of planktonic siphonophores. Early juveniles may also exploit productive surface waters for faster growth before transitioning to deeper zones. Because of their lower activity levels, the family is thought to comprise ambush predators.

Migration

As they develop, glass squids often exhibit a two-phase life cycle: juveniles in the epipelagic layers, then migrating into bathypelagic waters as adults. By remaining translucent and harnessing specialized buoyancy mechanisms involving ammonia retention, cranchiids reduce energy expenditure and adapt to low-light deep-sea habitats. This vertical migration strategy is thought to minimize predation risk while maximizing feeding opportunities.

Reproduction

In terms of reproduction, Galiteuthis glacialis (one such example of Cranchiidae) exhibits unique strategies adapted to the deep-sea environment. Spawning occurs in the bathypelagic zone, where females release eggs in a single batch—a process known as synchronous ovulation. Post-spawning, females undergo tissue degeneration, leading to increased buoyancy and causing them to ascend toward the surface. This phenomenon may explain the higher capture rates of mature females compared to males, which are hypothesized to die and sink to the seafloor after mating.

Genera

The family contains two subfamilies (both established by Georg Johann Pfeffer) and about 15 genera:

- Subfamily Cranchiinae

- Genus Cranchia

- Genus Leachia

- Genus Liocranchia

- Subfamily Taoniinae

- Genus Bathothauma

- Genus Belonella

- Genus Egea

- Genus Galiteuthis

- Genus Helicocranchia

- Genus Liguriella

- Genus Megalocranchia

- Genus Mesonychoteuthis

- Genus Sandalops

- Genus Taonius

- Genus Teuthowenia

- Parateuthis tunicata (incertae sedis)