Language shift

Language shift, also known as language transfer, language replacement or language assimilation, is the process whereby a speech community shifts to a different language, usually over an extended period of time. Often, languages that are perceived to be of higher-status stabilize or spread at the expense of other languages that are perceived by their own speakers to be of lower-status. An example is the shift from Gaulish to Latin during the time of the Roman Empire.

Mechanisms

Prehistory

For prehistory, Forster et al. (2004) and Forster and Renfrew (2011) observe that there is a correlation of language shift with intrusive male Y chromosomes but not necessarily with intrusive female mtDNA. They conclude that technological innovation (the transition from hunting-gathering to farming, or from stone to metal tools) or military prowess (as in the abduction of British women by Vikings to Iceland) causes immigration of at least some men, who are perceived to be of higher status than local men. Then, in mixed-language marriages, children would speak the "higher-status" language, yielding the language/Y-chromosome correlation seen today.

Assimilation is the process whereby a speech-community becomes bilingual and gradually shifts allegiance to the second language. The rate of assimilation is the percentage of the speech-community that speaks the second language more often at home. The data are used to measure the use of a given language in the lifetime of a person, or most often across generations. When a speech-community ceases to use their original language, language death is said to occur.

Indo-European migrations

In the context of the Indo-European migrations, it has been noted that small groups can change a larger cultural area. Michael Witzel refers to Ehret's model "which stresses the osmosis, or a "billiard ball," or Mallory's Kulturkugel, effect of cultural transmission." According to Ehret, ethnicity and language can shift with relative ease in small societies, due to the cultural, economic and military choices made by the local population in question. The group bringing new traits may initially be small, contributing features that can be fewer in number than those of the already local culture. The emerging combined group may then initiate a recurrent, expansionist process of ethnic and language shift.

David Anthony notes that the spread of the Indo-European languages probably did not happen through "chain-type folk migrations", but by the introduction of these languages by ritual and political elites, which are emulated by large groups of people. Anthony explains:

Anthony gives the example of the Luo-speaking Acholi in northern Uganda in the 17th and 18th century, whose language spread rapidly in the 19th century. Anthony notes that "Indo-European languages probably spread in a similar way among the tribal societies of prehistoric Europe", carried forward by "Indo-European chiefs" and their "ideology of political clientage". Anthony notes that "elite recruitment" may be a suitable term for this system.

Modern society

In urban settings, language change occurs due to the combination of three factors: the diversity of languages spoken, the high population density, and the need for communication. Urban vernaculars, urban contact varieties, and multiethnolects emerge in many cities around the world as a result of language change in urban settings. These factors lead to phenomena such as dialect levelling, koineization, and/or language shift toward a dominant language.

Examples

Liturgical language

Historical examples for status shift are the early Welsh and Lutheran Bible translations.

Austria

Until the mid-19th century, southern Carinthia in Austria had an overwhelming Slovene-speaking majority: in the 1820s, around 97% of the inhabitants south of the line Villach-Klagenfurt-Diex spoke Slovene as their native language. In the course of the 19th century, this number fell significantly. By 1920, a third of the population of the area had already shifted to German as their main language of communication. After the Carinthian Plebiscite in the 1920s, and especially after World War II, most of the population shifted from Slovene to German. In the same region, today only some 13% of the people speak Slovene, while more than 85% of the population speak German. The figures for the whole region are equally telling: in 1818, around 35% of the population of Carinthia spoke Slovene; by 1910, this number had fallen to 15.6% and by 2001 to 2.3%. These changes were almost entirely the result of a language shift in the population, with emigration and genocide (by the Nazis during World War II) playing only a minor role.

Belarus

Despite the withdrawal of Belarus from the USSR proclaimed in 1991, use of the Belarusian language is declining. According to the 2009 Belarusian population census, 72% of Belarusians speak Russian at home, and Belarusian is used by only 11.9% of Belarusians. 52.5% of Belarusians can speak and read Belarusian. Only 29.4% can speak, read and write it. One in ten Belarusians do not understand the Belarusian language.

Belgium

In the last two centuries, Brussels has transformed from an exclusively Dutch-speaking city to a bilingual city with French as the majority language and lingua franca. The language shift began in the 18th century and accelerated as Belgium became independent and Brussels expanded out past its original city boundaries. From 1880 on, more and more Dutch-speaking people became bilingual, resulting in a rise of monolingual French-speakers after 1910.

Halfway through the 20th century, the number of monolingual French-speakers began to predominate over the (mostly) bilingual Flemish inhabitants. Only since the 1960s, after the establishment of the Belgian language border and the socio-economic development of Flanders took full effect, could Dutch use stem the tide of increasing French use. French remains the city's predominant language, while Dutch is spoken by a minority.

Canada

China

Historically, one of the most important language shifts in China has been the near disappearance of the Manchu language. When China was ruled by the Qing dynasty, whose Emperors were Manchu, Chinese and Manchu had co-official status, and the Emperor heavily subsidized and promoted education in Manchu, but because most of the Manchu Eight Banners lived in garrisons with Mandarin-speaking Han Bannermen located across Han Chinese civilian populated cities, most Manchus spoke the Beijing dialect of Mandarin by the 19th century and the only Manchu speakers were garrisons left in their homeland of Heilongjiang. Today there are fewer than 100 native speakers of Manchu.

At the current time, language shift is occurring all across China. Many languages of minority ethnic groups are declining, as well as the many regional varieties of Chinese. Generally the shift is in favour of Standard Chinese (Mandarin), but in the province of Guangdong the cultural influence of Cantonese has meant local dialects and languages are being abandoned for Cantonese instead.

Languages like Tujia and Evenki are also disappearing due to language shift.

- Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, Cantonese has become the dominant language spoken in society since widespread immigration to Hong Kong began in the 1940s. With immigrants of differing mother tongues, communication was hard without a dominant language. Cantonese originated from the capital of neighboring Canton province, and it became the dominant language by extension, and other similar dialects started to vanish from use in Hong Kong. Original residents, or aboriginals, of Hong Kong used their own languages including the Tanka, Hakka and Waitau dialect, but with a majority of Hong Kong's population being immigrants by the 1940s and 50s, these dialects rapidly vanished. Most of Hong Kong's younger generation does not understand, let alone speak, their ancestral dialects.

Beginning in the late 1990s, since Hong Kong's return to Chinese sovereignty, Mandarin Chinese has been more widely implemented in education and many other areas of official society. Though Mandarin Chinese has been quickly adopted into society, most Hong Kong residents would not regard it as a first language/dialect. Most Hong Kong residents prefer to communicate in Cantonese in daily life.

Speakers of Mandarin Chinese and of Cantonese cannot mutually understand each other without learning the languages, due to vast differences in pronunciation, intonation, sentence structure and terminology. Furthermore, cultural differences between Hong Kong and China result in variations between the Cantonese used in Hong Kong and that in Canton Province.

Egypt

In Egypt, the Coptic language, a descendant of the Afro-Asiatic Egyptian language, has been in decline in usage since the time of the Arab conquest in the 7th century. By the 17th century, it was eventually supplanted as a spoken language by Egyptian Arabic. Coptic is today mainly used by the Coptic Church as a liturgical language. In the Siwa Oasis, a local variety of Berber is also used alongside Arabic.

Ethiopia

In Ethiopia, various populations of Nilotic origin have shifted languages over the centuries, adopting the idioms of their Afro-Asiatic-speaking neighbors in the northern areas. Among these groups are the Daasanach or Marille, who today speak the Daasanach language. It belongs to the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic family. However, modern genetic analysis of the Daasanach indicates that they are more closely related to Nilo-Saharan and Niger-Congo-speaking populations inhabiting Tanzania than they are to the Cushitic and Semitic Afro-Asiatic-speaking populations of Ethiopia. This suggests that the Daasanach were originally Nilo-Saharan speakers, sharing common origins with the Pokot. In the 19th century, the Nilotic ancestors of these two populations are believed to have begun separate migrations, with one group heading southwards into the African Great Lakes region and the other group settling in southern Ethiopia. There, the early Daasanach Nilotes would have come into contact with a Cushitic-speaking population, and eventually adopted this group's Afro-Asiatic language.

Finland

Finland still has coastal Swedish-speaking enclaves, unlike Estonia where the last coastal Swedes were decimated or escaped to Sweden in 1944. As Finland was part of the Sweden realm from the Middle Ages until 1809, the language of education was Swedish, with Finnish being allowed as a medium of education at the university only in the 19th century, and the first thesis in Finnish being published in 1858. Several of the coastal cities were multilingual; Viipuri had newspapers in Swedish, Finnish, Russian and German. However, the industrialization in the prewar era and especially the postwar era and the "escape from the countryside" of the 1960s changed the demography of the major cities and led to Finnish dominating. While Helsinki was a predominantly Swedish-speaking city prior to the turn of the 20th century, the Swedish-speaking minority is now about 6% of the population.

France

- Alsace and Lorraine

In Alsace, France, a longtime Alsatian-speaking region, the native Germanic dialect has been declining after a period of being banned at school by the French government after the First World War and the Second World War. It is being replaced by French.

- French Flanders

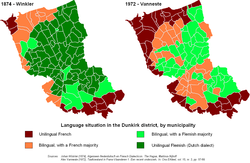

French Flanders, which gradually became part of France between 1659 and 1678, was historically part of the Dutch sprachraum, the native dialect being West Flemish (French Flemish). This is corroborated by the Dutch origin of several town names in the region, such as that of 'Dunkerque' (Dunkirk) which is a French phonetic rendition of the original Dutch name 'Duinkerke' (meaning 'church in the dunes'). The linguistic situation did not change dramatically until the French Revolution in 1789, and Dutch continued to fulfill the main functions of a cultural language throughout the 18th century. During the 19th century, especially in the second half of it, Dutch was banned from all levels of education and lost most of its functions as a cultural language. The larger cities had become predominantly French-speaking by the end of the 19th century.

However, in the countryside, many elementary schools continued to teach in Dutch until World War I, and the Roman Catholic Church continued to preach and teach the catechism in Flemish in many parishes. Nonetheless, since French enjoyed a much higher status than Dutch, from about the interbellum onward, everybody became bilingual, the generation born after World War II being raised exclusively in French. In the countryside, the passing on of Flemish stopped during the 1930s or 1940s. Consequently, the vast majority of those still having an active command of Flemish are older than 60. Therefore, complete extinction of French Flemish can be expected in the coming decades.

- Basque Country

The French Basque Country has been subject to intense French-language pressure exerted over the Basque-speaking communities. In the late 1800s, the Basque language was both persecuted and excluded from administration and official public use during the takeover of the National Convention, during the War of the Pyrenees, and during the Napoleonic period. The compulsory national education system imposed early on a French-only approach (mid-19th century), marginalizing Basque, and by the 1960s family transmission was grinding to a halt in many areas at the feet of the Pyrenees.

By the 2010s, the receding trend has been somewhat mitigated by the establishment of Basque schooling (the ikastolak) spearheaded by the network Seaska, as well as the influence of the Basque territories from Spain.

- Brittany

According to Fañch Broudic, Breton has lost 80% of its speakers in 60 years. Other sources mention that 70% of Breton speakers are over 60. Furthermore, 60% of children received Breton from their parents in the 1920s and only 6% in the 1980s. Since the 1980s, monolingual speakers are no longer attested.

On the 27 October 2015, the Senate rejected the draft law on ratification of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages driving away the assumption of Congress for[clarification needed] the adoption of the constitutional reform which would have given value and legitimacy to regional languages such as Breton.

- Corsica

Corsican was long employed as a conglomerate of local vernaculars in combination with Italian, the official language in Corsica until 1859; afterwards Italian was replaced by French, owing to the acquisition of the island by France from Genoa in 1768. Over the next two centuries, the use of French grew to the extent that, by the Liberation in 1945, all islanders had a working knowledge of French. The 20th century saw a wholesale language shift, with islanders changing their language practices to the extent that there were no monolingual Corsican speakers left by the 1960s. By 1995, an estimated 65 percent of islanders had some degree of proficiency in Corsican, and a small minority, perhaps 10 percent, used Corsican as a first language.

- Occitania

Germany

- Southern Schleswig

In Southern Schleswig, an area that belonged to Denmark until the Second Schleswig War, there was a language shift from the 17th to the 20th centuries from Danish and North Frisian dialects to Low German and later High German. Historically, most of the region was part of the Danish and North Frisian language area, adjacent in the south to the German-speaking Holstein. But with the Reformation in the 16th century German became the language of the Church, and in the 19th century also that of schools in the southern parts of Schleswig. Added to this was the influence of German-speaking Holsatian nobility and traders. German was (occasionally) also spoken at the royal court in Copenhagen. This political and economic development led gradually to a German language dominating in the southern parts of Schleswig. Native dialects such as the Angel Danish and Eiderstedt Frisian vanished. In the Flensburg area, there arose the mixed language Petuh combining Danish and German elements. As late as in 1851 (in the period of nationalization) the Danish government tried to stop the language shift, but without success in the long run. After the Second Schleswig War the Prussians introduced a number of language policy measures in the opposite direction to expand the use of (High) German as the language of administration, schooling and church services.

Today, Danish and North Frisian are recognized as minority languages in the federal state of Schleswig-Holstein.

Hungary

Cumans, seeking refuge from the Mongols, settled in Hungary and were later Magyarized. The Jassic people of Hungary originally spoke the Jassic dialect of Ossetic, but they fully adopted Magyar, forgetting their former language. The territory of today's Hungary was formerly settled by Slavonic tribes, which gradually assimilated to Magyar. Also, language shift may have happened in Hungarian pre-history, as the prehistoric culture of Magyars shows very little similarity to that of speakers of other Uralic languages.

India

In India, many languages are assimilated into standard language like Hindi, Bengali and other administrative languages. For example, the Austroasiatic-speaking Bhumij tribe for over two centuries nearly abandoned their native language and adopted Bengali and Odia instead. Today, the Bhumij language is one of the endangered languages of India.

Indonesia

Indonesia is one of the most multilingual and multiethnic nations in the world. There is language shift of first language into Indonesian from other language in Indonesia caused by ethnic diversity than urbanicity. Regardless of urbanicity, Indonesian speakers are more prevalent in urban areas than rural ones. The study found that language shift is mainly occurring among Javanese people and in districts where Javanese is the dominant language, which is not what was expected. Another study suggests Javanese youths do not value Javanese language and culture as much as the national Indonesian language and culture because they perceive them as outdated and incompatible with modern society.

Ireland

Israel

An example is the shift from Canaanite and Phoenician and Hebrew to Aramaic in and around Jerusalem during the time of Classical Antiquity. Another example is during the Middle Ages, when shifting from Aramaic to Arabic through the advent of Islam. A third shift took place in Modern times, under the influence of Zionism, from Jewish languages such as Yiddish, Ladino and various dialects of Judeo-Arabic to Modern Hebrew.

Italy

The Italian peninsula, the Po river basin and the nearby islands are home to various languages, most of which are Latin-derived. Italy would be politically organized into states until the late 19th century.

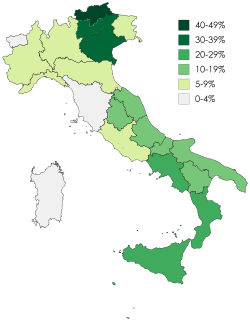

Since the times of the Renaissance, a trans-Italian language was developed in central Italy, based on Florentine Tuscan; in light of its cultural prestige, it was used for formal, literary and written purposes among the literate classes from the various states of mainland Italy, Sicily and Corsica (France), sidelining the other dialects in education and formal settings. Thus, literary Florentine was established as the most representative dialect of Italy long before its political unification in 1861, Tuscan having been officially adopted by the preunitarian states. Italian further expanded as a common language for everyday use throughout the country after World War II.

Most other languages, with the exception of those spoken by specific ethno-linguistic groups, long served as local vernaculars alongside Italian; therefore they have been mislabelled "dialects" by their own speakers, but they are still usually spoken just as much as standard Italian in a diglossic spectrum with little conflict.

For instance, the local Venetian dialects in Northeast Italy are widely used and locally promoted in the region; after all, Italian had been an integral part of the Republic of Venice since the 14th century, whose elites used to revere the most prominent Tuscan authors and tuscanize their own speech as well. On a survey made by Il Gazzettino in 2015, 70% of respondents told they spoke Venetian "very or quite often" in the family, while 68% with friends. A much lower percentage reported to use it at work (35%); the local language is less used in formal situations. However, the frequency of use within the family networks and friendship stopped respectively at -4 and -11 percentage points, suggesting a slow morphing to Italian, while the use in the workplace dropped to -22 percentage points. A visible generational gap has also been noted, since the students and young people under the age of 25 are the social group where the use of dialect fell below the threshold of absolute majority (respectively 43 and 41%). Nonetheless, despite some tendencies signalling the slow advancement of standard Italian, the local dialects of Veneto and the Province of Trieste are still widely spoken alongside Italian; like in much of Italy, the presence of Italian in Northeast Italy does not seem to take anything away from the region's linguistic heritage.

Like the aforementioned case of Northeast Italy, even in Southern Italy and Sicily the local dialects from the Italo-Dalmatian family are widely used in combination with standard Italian, depending upon the social context. More specifically, Italian as the prevalent language spoken among family members is spoken the least in Campania (20.7%), Calabria (25.3%) and Sicily (26.6%), contrary to frequency of use of the local dialects (Basilicata, 69.4%; Calabria 68.6%; Campania, 75.2%; Sicily, 68.8%).

- Germanic languages

Trentino's Cimbrian, a Germanic language related to Bavarian, was spoken by at least 20,000 people in the 19th century, with 3,762 people in 1921 and fewer than 300 in 2007. The same scenario goes for Mòcheno and Walser.

- Sardinia

Unlike the neighbouring island of Corsica (France) and elsewhere in today's Italy, where Italian was the standard language shared by the various local elites since the late Middle Ages, Italian was first officially introduced to Sardinia, to the detriment of both Spanish and Sardinian (the only surviving Neo-Latin language from the Southern branch), only in 1760 and 1764 by the then-ruling House of Savoy, from Piedmont. Because of the promotion and enforcement of the Italian language and culture upon the Sardinian population since then, the majority of the locals switched over to such politically dominant language and no longer speak their native ones, which have seen steady decline in use. The language has been in fact severely compromised to the point that only 13% of the children are able to speak it, and today is mostly kept as a heritage language. With the exception of a few sparsely populated areas where Sardinian can still be heard for everyday purposes, the island's indigenous languages have by now been therefore largely replaced by Italian; the language contact ultimately resulted in the emergence of a specific variety of Italian, slightly divergent from the standard one.

Lithuania

Due to language shift, ethnographic borders of Lithuanian language from the Middle Ages to the late 1930s shrank sharply to the north and west from the territory what is now Grodno oblast in Belarus, giving way to the spreading Polish and Belarusian languages, while in Prussian Lithuania out of 10 administrative units with prevailing Lithuanian language in the early 1800s, only the extreme northern part – Klaipėda region had still relative Lithuanian language majority in the 1910s with all the eastern and southern territories in some hundred or so years almost fully Germanized. These processes were happening both because of the perception of population as Lithuanian language was seen as of lower status by its peripheral speakers as well as deliberate policy by German and Russian imperial administrations, notably – a 40-year ban on Lithuanian language and press by the Tsarist government. In Lithuania Minor, where Lithuanian culture began to decline after The Great Plague between 1708 and 1711, Kristijonas Donelaitis' poem – The Seasons addressed this issue. In Northern Poland during the Middle Ages, the territory of Lithuanian language was reaching vicinities of Łomża, Tykocin and Białystok, but shrank to the north – to the rural outskirts of Sejny, Punsk and Wiżajny before the 1900s as a consequence of acculturation. The Polish-speaking island to the north of Kaunas and south of Panevėžys almost fully disappeared between the 1920s and the 1940s, as the local Lithuanian population, who increasingly began to speak Polish on a daily basis and at home during the 19th century (especially after the 1831 November Uprising and the 1863 January Uprising) gradually returned back to the Lithuanian language.

Malta

Before the 1930s, Italian was the only official language of Malta, although it was spoken only by the upper class, with Maltese being spoken by the lower class. Even though English has replaced Italian as a co-official language alongside Maltese, the Italian-speaking population has since grown, but the growth of English in the country now threatens the status of Maltese. A trend among the younger generations is to mix English and Italian vocabulary patterns, in making new Maltese words. For example, the Maltese word bibljoteka has been overtaken by librerija, formed from library with an Italian ending. In addition to mixing English with Italian, Maltenglish involves the use of English words in Maltese sentences. Trends show that English is becoming the language of choice for more and more people, and is transforming the Maltese language.

Pakistan

Urdu, the lingua franca of South Asian Muslims and the official and national language of Pakistan since its independence, is spoken by most educated Pakistanis. Despite positive attitudes towards Punjabi in the urban areas of Pakistani Punjab, there is a shift towards Urdu in almost all domains. Pashtuns and other minorities in northern Pakistan use Urdu as a replacement for former native languages.

Paraguay

Guarani, an indigenous language of South America belonging to the Tupi–Guarani family of the Tupian languages, and specifically the primary variety known as Paraguayan Guarani (endonym avañe'ẽ [aʋãɲẽˈʔẽ]; 'the people's language'), is one of the official languages of Paraguay (along with Spanish), where it is spoken by the majority of the population, and where half of the rural population is monolingual. Guarani is one of the most-widely spoken indigenous languages of the Americas and the only one whose speakers include a large proportion of non-indigenous people. This represents a unique anomaly in the Americas, where language shift towards European colonial languages has otherwise been a nearly universal cultural and identity marker of mestizos (people of mixed Spanish and Amerindian ancestry), and also of culturally assimilated, upwardly mobile Amerindian people.

Paraguayan Guarani has been used throughout Paraguayan history as a symbol of nationalistic pride. Populist dictators such as José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia and Alfredo Stroessner used the language to appeal to common Paraguayans, and upon the advent of Paraguayan democracy in 1992, Guarani was enshrined in the new constitution as a co-equal language along with Spanish. Jopara, the mixture of Spanish and Guarani, is spoken by an estimated 90% of the population of Paraguay. Code-switching between the two languages takes place on a spectrum where more Spanish is used for official and business-related matters, whereas more Guarani is used in art and in everyday life.

Parthia

Instances of language shift appear to have occurred twice in the history of the Parthian Empire: once before its foundation, when the Parni invaded Parthia, eventually losing their Eastern Middle Iranian language and adopting Parthian instead; secondly, after the fall of the Parthian Empire, Parthian speakers shifted to Middle Persian or Armenian.

Philippines

In the Philippines, Spanish-speaking families have gradually switched over to Tagalog or English since the end of World War II, so Spanish has ceased to be a practical everyday language in the country and is on the verge of extinction.

Another example would be the gradual death of the Kinaray-a language of Panay as many native speakers especially in the province of Iloilo are switching to Hiligaynon or mixing the two languages together. Kinaray-a was once spoken in the towns outside the vicinity of Iloílo City, while Hiligaynon was limited to only the eastern coasts and the city proper. However, due to media and other factors such as urbanization, many younger speakers have switched from Kinaray-a to Hiligaynon, especially in the towns of Cabatuan, Santa Barbara, Calinog, Miagao, Passi City, Guimbal, Tigbauan, Tubungan, etc. Many towns, especially Janiuay, Lambunao, and San Joaquin still have a sizeable Kinaray-a-speaking population, with the standard accent being similar to that spoken in the predominantly Karay-a province of Antique. Even in the province of Antique, "Hiligaynonization" is an issue to be confronted as the province, especially the capital town of San José de Buenavista, undergoes urbanisation. Many investors from Iloílo City bring with them Hiligaynon-speaking workers who are reluctant to learn the local language.

One of the problems of Kinaray-a is its written form, as its unique "schwa sound" is difficult to represent in orthography. As time goes by, Kinaray-a has disappeared in many areas it was once spoken especially in the island of Mindoro and only remnants of the past remain in such towns as Pinamalayan, Bansud, Gloria, Bongabong, Roxas, Mansalay, and Bulalacao in Oriental Mindoro and Sablayan, Calintaan, San Jose, and Magsaysay in Occidental Mindoro, as Tagalog has become the standard and dominantly recognised official language of these areas.

Palawan has 52 local languages and dialects. Due to this diversity, internal migration and mass media, Tagalog has effectively taken over as the lingua franca on the island. Same case what happened to Mindanao, it has many native languages and dialects but due to internal migration which started during Spanish era until to this day from people of Visayas and Visayan languages suddenly became the widely spoken languages in the island and some of the local languages are getting influenced and slowly losing its original form.

In Luzon, the provinces of Camarines Norte, Camarines Sur, and Pampanga have seen a shift to Tagalog. Similarly, younger generations in Davao City are increasingly shifting from Cebuano to Tagalog as their primary language.

Romania

The localized version of Latin emerged from the interaction of indigenous people and the Roman state over a long stretch of time — including a long time after the Roman army withdrew from to the southern shore of the Danube in 271.

Russia

Since the rule of Catherine II, the Russian government has been making continuous efforts at Russification of its numerous subjects.

Nowadays, there is a persistent drop in percentage of speakers of languages other than Russian.

Singapore

After Singapore's independence in 1965, there was a general language shift in the country's interracial lingua franca from Malay to English, which was chosen as the first language for the country. Among the Chinese community in Singapore, there was a language shift from the various dialects of Chinese to English and Mandarin Chinese. Until the 1980s, Singaporean Hokkien was the lingua franca of Chinese community in Singapore, which has since been replaced with English and Mandarin today. There has been a general language attrition in the use of Chinese other than Mandarin Chinese, especially amongst the younger segments of the Singaporean population.

Spain

The progressive dominion exerted by the Kingdom of Castile over Spain in as much as it gained political power throughout centuries, contributed to the expansion of its language at the expenses of the rest. The accession of the Castilian House of Trastamara to the Crown of Aragon by the mid-15th century saw the gradual displacement of the royal languages of the Crown of Aragon, Aragonese and Catalan, despite the prolific Valencian literature in Catalan in this period. Nebrija's Gramatica castellana (1492), sponsored by the new Spanish monarch Ferdinand II of Aragon, was meant to help expand Castilian, "the companion of the Empire". As the Crown of Castile expanded, its different governmental officials at different levels required their subjects to use or understand Castilian and sideline other vulgar languages, or vernaculars. It often meant the use of interpreters in lawsuits, which could tilt the outcome of the case, e.g. the Basque witch trials, and the increased use of Castilian in assemblies and decision-making bodies, and documents, despite not being the commonly understood language in a number of areas, like most of the Basque districts (Navarre, Álava, etc.), Catalonia, Galicia, Asturias, parts of Aragon, etc.

As Aragonese retreated to the sub-Pyrenean valleys, Arabic vanished by the early 17th century, when forced cultural assimilation of the Moriscos was coupled with expulsion (completed in 1614). The arrival of the Bourbons (1700) intensified the centralization of governmental structures and the imposition of Castilian as the only language for official purposes, replacing in 1716 Catalan as the language of Justice Administration in the relevant territories (Nueva Planta Decrees). Unlike Catalan, Basque was never a language written on official documents, but was equally affected. It lost ground to Castilian in all its buffer geographic areas, as well as main institutions as a communication language, after a number of decrees and orders established Castilian as "the national language of the Empire" during Charles III's reign; printing in languages other than Spanish was forbidden (1766), and Castilian was the only language taught in school (1768).

The Peninsular War was followed by the centralization of Spain (Constitutions of 1812, 1837, 1845, 1856, etc.), with only the Basque districts keeping a separate status until 1876. Compulsory education in 1856 made the use of Castilian (Spanish) mandatory, as well as discouraging and forbidding the use of other languages in some social and institutional settings. Franco and his nationalist dictatorship imposed Spanish as the only valid language for any formal social interaction (1937). By the early 21st century, Spanish was the overwhelmingly dominant language in Spain, with Basque, Catalan, and Galician surviving and developing in their respective regions with different levels of recognition since 1980. Other minorized languages (Asturian, Aragonese) have also seen some recognition in the early 21st century. Catalan, sharing with Basque a strong link between language and identity (especially in Catalonia), enjoys a fairly sound status, however many Catalan speakers think that their language is still in danger, and this perception has brought about a number of campaigns to promote the use of Catalan, for instance Mantinc el català. Basque competence has risen during the last decades, but daily use has not risen accordingly. The Endangered Languages Project has classified Asturian as being at risk and Aragonese as endangered.

Taiwan

Taiwanese aborigines used only Austronesian languages before other ethnic groups conquered Taiwan. After widespread migration of Han peoples from the 17th to the 19th century, many Taiwanese Plains Aborigines became Sinicized, and shifted their language use to other Sinitic tongues, (mainly Taiwanese Hokkien). Additionally, some Hakka people (a Han Chinese ethnic subgroup) also shifted from Hakka Chinese to Hokkien (also called Hoklo). This happened especially in Yongjing, Changhua, Xiluo, Yunlin, etc. They are called Hoklo-Hakka (Phak-fa-sṳ: Hok-ló-hak, Peh-oē-jī: Hô-ló-kheh, Hanzi: 福佬客).

When Taiwan was under Japanese rule, Japanese became the official language, with the Japanese government promoting Japanese language education. It also led to the creation of Yilan Creole Japanese, a mixture of Japanese, Atayal language, and Hokkien in Yilan County. In World War II, under the Japanification Movement, Chinese was banned in newspapers and school lectures, and the usage of Japanese at home was encouraged, so many urban people turned to using Japanese. In 1941, 57% of Taiwanese could speak Japanese.

After the ROC government established rule over Taiwan in 1945, it forbade the use of Japanese in newspapers and schools, and promoted the Guoyu movement (Chinese: 國語運動) to popularize Standard Mandarin, often through coercive means. In the primary education system, people using local languages would be fined or forced to wear a dialect card. In the mass media, local languages were also discouraged or banned, and some books on the romanization of local languages (e.g. Bibles, lyrics books, Peh-ōe-jī) were banned. In 1975, The Radio and Television Act (Chinese: 廣播電視法) was adopted, restricting the usage of local languages on the radio or TV. In 1985, after the draft of the Language and Script Law (Chinese: 語文法) was released by the Ministry of Education, it received considerable opposition because it banned the use of Taiwanese unofficial languages in the public domain. In response, some Hakka groups demonstrated to save their language. After 1987 when martial law was lifted, the Guoyu movement ceased.

The shift towards monolingual Mandarin was more pronounced among Hakka-speaking communities, attributed to Hakka's low social prestige. Before the KMT took over the island from Japan, the Hakka were expected to learn both Hokkien and Japanese. However, the lack of a significant Japanese-speaking base for gaining and then retaining Japanese fluency meant that most Hakka learned only Hokkien. When the KMT fled to Taiwan from mainland China, most mainlanders settled mainly in northern Taiwan, close to Hakka-speaking areas, thus spurring a linguistic shift from Hokkien to Mandarin within the Taipei area. As the bulk of economic activity centered around patronage networks revolving around Mandarin-speaking KMT membership, most of the Hakka became Mandarin monolinguals, due to a shift in social mobility formerly centered around Hokkien. Elsewhere, although the Hokkien speech-community shrank within the population, most Hokkien-speaking households have retained fluency in Hokkien, helped by the liberalization of Taiwanese politics and the end of martial law.[specify]

Nevertheless, Taiwanese Mandarin has become the most common language in Taiwan today, and the most common home language of Taiwanese youth. In the population census of 2010, Mandarin is the most common home language in the Taipei metropolitan area, Taoyuan, Matsu, aboriginal areas, some Hakka-majority areas, as well as some urban areas of Taichung and Kaohsiung. Conversely, the ability of Taiwanese to speak ethnic languages is strikingly on the decline.

Turkey

Studies have suggested an elite cultural dominance-driven linguistic replacement model to explain the adoption of Turkish by Anatolian indigenous inhabitants.

During the presidency of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, policy of turkification was heavily promoting thus leading to languages of Muhacirs disappearing.

United Kingdom

The island of Great Britain, located on the western fringes of Northwestern Europe, has experienced a series of successive language changes and developments in the course of several invasions. Celtic languages predominated before the arrival of the Romans in 43 CE imposed a Latinate superstructure. Anglo-Saxon dialects then swamped much of the Romano-British speech from the 5th century, only to be challenged from the 9th century by the influx of Old Norse dialects in much of England and in parts of Scotland. Following the Norman invasion of the 11th century, Norman-French became the prestige tongue, with Middle English re-asserting the Germanic linguistic heritage gradually in the course of the later Middle Ages.

- Cornwall

- Scottish Gaelic

Gaelic has long suffered from its lack of use in educational and administrative contexts, and was long suppressed by Scottish and then British authorities. The shift from Gaelic to Scots and Scottish English has been ongoing since about 1200 CE; Gaelic has gone from being the dominant language in almost all areas of present-day Scotland to an endangered language spoken by only about 1% of the population.

With the advent of Scottish devolution, however, Scottish Gaelic has begun to receive greater attention, and it achieved a degree of official recognition when the Scottish Parliament enacted the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act on 21 April 2005. Gaelic-medium education in Scotland now enrolls more than 2000 students a year. Nevertheless, the number of Gaelic native speakers continues to decline, and Scottish Gaelic is[when?] a minority language in most of the traditional Gàidhealtachd, including all census areas outside of the Outer Hebrides.

- London

Predictions envisage the replacement of Cockney English (traditionally spoken by working-class Londoners) by Multicultural London English (MLE) or "Jafaican" by about 2040 as Cockneys move out of London. Researchers theorise that the new language emerged as new migrants spoke their own forms of English such as Nigerian and Pakistani English, and that it contains elements from "learners' varieties" as migrants learn English as a second language.

- Wales

United States

Although English has been the majority language in the United States since independence in 1776, hundreds of aboriginal languages were spoken before western European settlement. French was once the main language in Louisiana, Missouri, and areas along the border with Quebec, but the speaking has dwindled after new waves of migration and the rise of English as a lingua franca. Californio Spanish became a minority language during the California Gold Rush; it has largely been overtaken by English and Mexican Spanish, surviving mainly as a prestige dialect in Northern and Central California. German was once the main language in large areas of the Great Plains and Pennsylvania, but it was suppressed by anti-German sentiment during the First World War. But contemporary English is widely used in the United States, and so many years of development have created the growth of English in the region.

Vietnam

Since the fall of Saigon at the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, French has declined heavily in Vietnam from being a government language and primary language of education in South Vietnam to being a minority language limited to the elite classes and elderly population. Today, French is spoken fluently by less than 1% of the Vietnamese population. The language shift from French to Vietnamese occurred earlier in the north due to Viet Minh and later communist policies enforcing Vietnamese as the language of politics and education. However, since the late 1990s, there has been a minor revival of French in Vietnam.

Reversing

American linguist Joshua Fishman has proposed a method of reversing language shift which involves assessing the degree to which a particular language is disrupted in order to determine the most appropriate method of revitalising.

See also

Notes

References

Sources

Further reading

- Fishman, Joshua A., LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE AND LANGUAGE SHIFT AS A FIELD OF INQUIRY. A DEFINITION OF THE FIELD AND SUGGESTIONS FOR ITS FURTHER DEVELOPMENT (PDF)

- Thomason, Sarah Grey; Kaufman, Terrence (1988), Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics, University of California Press (published 1991), ISBN 978-0-520-07893-2

- Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.), Archaeology and Language, vol. IV: Language Change and Cultural Transformation, London: Routledge, pp. 138–148

- Bastardas-Boada, Albert. From language shift to language revitalization and sustainability. A complexity approach to linguistic ecology. Barcelona: Edicions de la Universitat de Barcelona, 2019.ISBN 978-84-9168-316-2