Plinian eruption

Plinian eruptions or Vesuvian eruptions are volcanic eruptions characterized by their similarity to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, which destroyed the ancient Roman cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii. The eruption was described in a letter written by Pliny the Younger, after the death of his uncle Pliny the Elder.

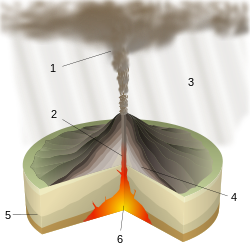

Plinian eruptions eject columns of volcanic debris and hot gases high into the stratosphere, the second layer of Earth's atmosphere. They eject a large amount of pumice and have powerful, continuous gas-driven eruptions.

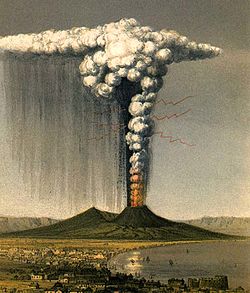

Eruptions can end in less than a day, or continue for days or months. The longer eruptions begin with production of clouds of volcanic ash, sometimes with pyroclastic surges. The amount of magma ejected can be so large that it depletes the magma chamber below, causing the top of the volcano to collapse, resulting in a caldera. Fine ash and pulverized pumice can be deposited over large areas. Plinian eruptions are often accompanied by loud sounds. The sudden discharge of electrical charges accumulated in the air around the ascending column of volcanic ashes also often causes lightning strikes, as depicted by the English geologist George Julius Poulett Scrope in his painting of 1822 or observed during 2022 Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha'apai eruption and tsunami.

The lava is usually dacitic or rhyolitic, rich in silica. Basaltic, low-silica lavas rarely produce Plinian eruptions unless specific conditions are met (low magma water content <2%, moderate temperature, and rapid crystallization); a recent basaltic example is the 1886 eruption of Mount Tarawera on New Zealand's North Island.

Pliny's description

Pliny the Younger described the initial observations of his uncle, Pliny the Elder, of the 79 AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius:

Pliny the Elder set out to rescue the victims from their perilous position on the shore of the Bay of Naples, and launched his galleys, crossing the bay to Stabiae (near the modern town of Castellammare di Stabia). Pliny the Younger provided an account of his death, and suggested that he collapsed and died through inhaling poisonous gases emitted from the volcano. His body was found buried under the ashes of the eruption with no apparent injuries on 26 August, after the plume had dispersed, which would be consistent with asphyxiation or poisoning, but also with a heart attack, asthma attack, or stroke.

Examples

- The Long Valley Caldera eruption in Eastern California, United States, which happened over 760,000 years ago.

- The 10,950 BC eruption of Lake Laach in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

- The 4860 BC eruption forming Crater Lake in Oregon, United States.

- The 1645 BC eruption of Thera in the south Aegean Sea, Greece.

- The 400s BC eruption of the Bridge River Vent in British Columbia, Canada.

- The 79 AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius in Pompeii, Italy. It was the prototypical Plinian eruption.

- The 180 AD Lake Taupo eruption in New Zealand.

- The 946 eruption of Paektu Mountain in China / North Korea.

- The 1257 eruption of Mount Samalas in Lombok, Indonesia.

- The 1600 eruption of Huaynaputina in Peru.

- The 1667 and 1739 eruptions of Mount Tarumae in Hokkaido, Japan.

- The 1707 eruption of Mount Fuji in Japan.

- The 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in the island of Sumbawa, Indonesia.

- The 1883 eruption of Krakatoa in Sunda Strait, Indonesia.

- The 1886 eruption of Mount Tarawera in New Zealand.

- The 1902 eruption of Santa María in Guatemala.

- The 1912 eruption of Novarupta in Alaska, United States, the largest volcanic eruption of the 20th century.

- The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington State.

- The 1982 eruption of El Chichón in Chiapanecan Volcanic Arc, Chiapas, Mexico.

- The 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in Zambales, Central Luzon, Philippines.

- The June 2009 eruption of Sarychev Peak in Russia.

- The 2011–2012 Puyehue-Cordón Caulle eruption in Chile.

- The 2014 eruption of Tungurahua volcano in Cordillera Oriental of Ecuador.

- The 2020 eruption of Taal Volcano in the Philippines.

- The 2022 eruption of Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha'apai in Tonga.

Ultra-Plinian

In 1980, the volcanologist George P. L. Walker proposed the Hatepe eruption as the representative of a new class called ultra-Plinian deposits, based on its exceptional dispersive power and eruptive column height. A dispersal index of 50,000 square kilometres (19,000 sq mi) has been proposed as a cutoff for an ultra-Plinian eruption. In the criteria of Volcanic Explosivity Index, recognizing an eruption as ultra-Plinian would make it at least VEI-5.

The threshold for ultra-Plinian eruptions is an eruptive column height of 45 km (28 mi), or 41 km (25 mi) more recently. The few instances of eruptions that lie at the transition between Plinian and ultra-Plinian include the P3 phase of 1257 Samalas eruption, 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo, the Plinian phase of the Campanian Ignimbrite, Tsankawi Pumice Bed of Tshirege Member of Bandelier Tuff, and the 1902 eruption of Santa María.

The once unequivocal ultra-Plinian classification of the Hatepe eruption has been called into question, with recent evidence showing that it is an artifact of an unrecognized shift in the wind field rather than extreme eruptive vigor.

See also

- Peléan eruption, related to the explosive eruptions of the Mount Pelée

- Types of volcanic eruptions

- List of largest volcanic eruptions