Yugoslav Partisans

The Yugoslav Partisans, officially the National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia (often shortened as the National Liberation Army) was the communist-led anti-fascist resistance to the Axis powers (chiefly Nazi Germany) in occupied Yugoslavia during World War II. Led by Josip Broz Tito, the Partisans are considered to be Europe's most effective anti-Axis resistance movement during World War II.

Primarily a guerrilla force at its inception, the Partisans developed into a large fighting force engaging in conventional warfare later in the war, numbering around 650,000 in late 1944 and organized in four field armies and 52 divisions. The main stated objectives of the Partisans were the liberation of Yugoslav lands from occupying forces and the creation of a federal, multi-ethnic socialist state in Yugoslavia.

The Partisans were organized on the initiative of Tito following the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941, and began an active guerrilla campaign against occupying forces after Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June. A large-scale uprising was launched in July, later joined by Draža Mihailović's Chetniks; this led to the creation of the short-lived Republic of Užice. The Axis mounted a series of offensives in response but failed to completely destroy the highly mobile Partisans and their leadership. By late 1943, the Allies had shifted their support from Mihailović to Tito as the extent of Chetnik collaboration became evident, and the Partisans received official recognition at the Tehran Conference. In Autumn 1944, the Partisans and the Soviet Red Army liberated Belgrade following the Belgrade Offensive. By the end of the war, the Partisans had gained control of the entire country as well as Trieste and Carinthia. After the war, the Partisans were reorganized into the regular armed force of the newly established Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia.

Objectives

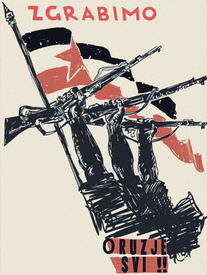

One of two objectives of the movement, which was the military arm of the Unitary National Liberation Front (UNOF) coalition, led by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ) and represented by the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ), the Yugoslav wartime deliberative assembly, was to fight the occupying forces. Until British supplies began to arrive in appreciable quantities in 1944, the occupiers were the only source of arms. The other objective was to create a federal multi-ethnic communist state in Yugoslavia. To this end, the KPJ attempted to appeal to all the various ethnic groups within Yugoslavia, by preserving the rights of each group.

The objectives of the rival resistance movement, the Chetniks, were the retention of the Yugoslav monarchy, ensuring the safety of ethnic Serb populations, and the establishment of a Greater Serbia through the ethnic cleansing of non-Serbs from territories they considered rightfully and historically Serbian. Relations between the two movements were uneasy from the start, but from October 1941 they degenerated into full-scale conflict. To the Chetniks, Tito's pan-ethnic policies seemed anti-Serbian, whereas the Chetniks' royalism was anathema to the communists. In the early part of the war Partisan forces were predominantly composed of Serbs. In that period names of Muslim and Croat commanders of Partisan forces had to be changed to protect them from their predominantly Serb colleagues.

After the German retreat forced by the Soviet-Bulgarian offensive in Serbia, North Macedonia, and Kosovo in the autumn of 1944, the conscription of Serbs, Macedonians, and Kosovar Albanians increased significantly. By late 1944, the total forces of the Partisans numbered 650,000 men and women organized in four field armies and 52 divisions, which engaged in conventional warfare. By April 1945, the Partisans numbered over 800,000.

Name

The movement was consistently referred to as the "Partisans" throughout the war. However, due to frequent changes in size and structural reorganizations, the Partisans throughout their history held four full official names (translated here from Serbo-Croatian to English):

- National Liberation Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia (June 1941 – January 1942)

- National Liberation Partisan and Volunteer Army of Yugoslavia (January – November 1942)

- National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia (November 1942 – February 1945). Increasingly from November 1942, the Partisan military as a whole was often referred to simply as the National Liberation Army (Narodnooslobodilačka vojska, NOV), whereas the term "Partisans" acquired a wider sense in referring to the entire resistance faction (including, for example, the AVNOJ).

- Yugoslav Army – on 1 March 1945, the National Liberation Army was transformed into the regular armed forces of Yugoslavia and renamed accordingly.

The movement was originally named National Liberation Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia (Narodnooslobodilački partizanski odredi Jugoslavije, NOPOJ) and held that name from June 1941 to January 1942. Because of this, their short name became simply the "Partisans" (capitalized), and stuck henceforward (the adjective "Yugoslav" is used sometimes in exclusively non-Yugoslav sources to distinguish them from other partisan movements).

Between January 1942 and November 1942, the movement's full official name was briefly National Liberation Partisan and Volunteer Army of Yugoslavia (Narodnooslobodilačka partizanska i dobrovoljačka vojska Jugoslavije, NOP i DVJ). The changes were meant to reflect the movement's character as a "volunteer army".

In November 1942, the movement was renamed into the National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia (Narodnooslobodilačka vojska i partizanski odredi Jugoslavije, NOV i POJ), a name which it held until the end of the war. This last official name is the full name most associated with the Partisans, and reflects the fact that the proletarian brigades and other mobile units were organized into the National Liberation Army (Narodnooslobodilačka vojska). The name change also reflects the fact that the latter superseded in importance the partisan detachments themselves.

Shortly before the end of the war, in March 1945, all resistance forces were reorganized into the regular armed force of Yugoslavia and renamed Yugoslav Army. It would keep this name until 1951, when it was renamed the Yugoslav People's Army.

Background and origins

On 6 April 1941, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was invaded from all sides by the Axis powers, primarily by German forces, but also including Italian, Hungarian and Bulgarian formations. During the invasion, Belgrade was bombed by the Luftwaffe. The invasion lasted little more than ten days, ending with the unconditional surrender of the Royal Yugoslav Army on 17 April. Besides being hopelessly ill-equipped when compared to the Wehrmacht, the Army attempted to defend all borders but only managed to thinly spread the limited resources available.

The terms of the capitulation were extremely severe, as the Axis proceeded to dismember Yugoslavia. Germany occupied the northern part of Drava Banovina (roughly modern-day Slovenia), while maintaining direct military occupation of a rump Serbian territory with a puppet government. The Independent State of Croatia (NDH) was established under German direction, which extended over much of the territory of today's Croatia and as well contained all the area of modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina and Syrmia region of modern-day Serbia. Mussolini's Italy occupied the remainder of Drava Banovina (annexed and renamed as the Province of Lubiana), much of Zeta Banovina and large chunks of the coastal Dalmatia region (along with nearly all its Adriatic islands). It also gained control over the newly created Italian governorate of Montenegro, and was granted the kingship in the Independent State of Croatia, though wielding little real power within it. Hungary dispatched the Hungarian Third Army and occupied and annexed the Yugoslav regions of Baranja, Bačka, Međimurje and Prekmurje. Bulgaria, meanwhile, annexed nearly all of Macedonia, and small areas of eastern Serbia and Kosovo. The dissolution of Yugoslavia, the creation of the NDH, Italian governorate of Montenegro and Nedic's Serbia and the annexations of Yugoslav territory by the various Axis countries were incompatible with international law in force at that time.

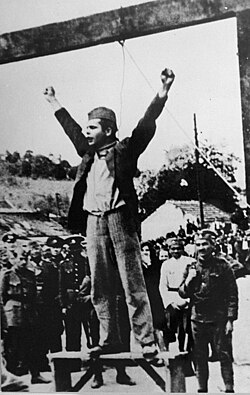

The occupying forces instituted such severe burdens on the local populace that the Partisans came not only to enjoy widespread support but for many were the only option for survival. Early in the occupation, German forces would hang or shoot indiscriminately, including women, children and the elderly, up to 100 local inhabitants for every one German soldier killed. While these measures for suppressing communist-led resistance were issued in all German-occupied territory, they were only strictly enforced in Serbia. Two of the most significant atrocities by the German forces were the massacre of 2,000 civilians in Kraljevo and 3,000 in Kragujevac. The formula of 100 hostages shot for every German soldier killed and 50 hostages shot for every wounded German soldier was cut in one-half in February 1943 and removed altogether in the fall of that same year.

Furthermore, Yugoslavia experienced a breakdown of law and order, with collaborationist militias roaming the countryside terrorizing the population. The government of the puppet Independent State of Croatia found itself unable to control its territory in the early stages of the occupation, resulting in a severe crackdown by the Ustaše militias and the German army.

Amid the relative chaos that ensued, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia moved to organize and unite anti-fascist factions and political forces into a nationwide uprising. The party, led by Josip Broz Tito, was banned after its significant success in the post-World War I Yugoslav elections and operated underground since. Tito, however, could not act openly without the backing of the USSR, and as the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact was still in force, he was compelled to wait.

Formation and early rebellion

During the April invasion of Yugoslavia, the leadership of the Communist Party was in Zagreb, together with Josip Broz Tito. After a month, they left for Belgrade. While the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between Germany and the Soviet Union was in effect, the communists refrained from open conflict with the new regime of the Independent State of Croatia. In these first two months of occupation, they extended their underground network and began amassing weapons. In early May 1941, a so-called May consultations of Communist Party officials from across the country, who sought to organize the resistance against the occupiers, was held in Zagreb. In June 1941, a meeting of the Central Committee of KPJ was also held, at which it was decided to start preparations for the uprising.

Operation Barbarossa, the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union, began on 22 June 1941.

The extent of support for the Partisan movement varied according to region and nationality, reflecting the existential concerns of the local population and authorities. The first Partisan uprising occurred in Croatia on 22 June 1941, when forty Croatian communists staged an uprising in the Brezovica woods between Sisak and Zagreb, forming the 1st Sisak Partisan Detachment.

The first uprising led by Tito occurred two weeks later, in Serbia. The Communist Party of Yugoslavia formally decided to launch an armed uprising on 4 July, a date which was later marked as Fighter's Day – a public holiday in the SFR Yugoslavia. One Žikica Jovanović Španac shot the first bullet of the campaign on 7 July in the Bela Crkva incident.

The first Zagreb-Sesvete partisan group was formed in Dubrava in July 1941. In August 1941, 7 Partisan Detachments were formed in Dalmatia with the role of spreading the uprising. On 26 August 1941, 21 members of the 1st Split Partisan Detachment were executed by firing squad after being captured by Italian and Ustaše forces. A number of other partisan units were formed in the summer of 1941, including in Moslavina and Kalnik. An uprising occurred in Serbia during the summer, led by Tito, when the Republic of Užice was created, but it was defeated by the Axis forces by December 1941, and support for the Partisans in Serbia thereafter dropped.

It was a different story for Serbs in Axis occupied Croatia who turned to the multi-ethnic Partisans, or the Serb royalist Chetniks. The journalist Tim Judah notes that in the early stage of the war the initial preponderance of Serbs in the Partisans meant in effect a Serbian civil war had broken out. A similar civil war existed within the Croatian national corpus with the competing national narratives provided by the Ustaše and Partisans.

In the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the cause of Serb rebellion was the Ustaše policy of genocide, deportations, forced conversions and mass killings of Serbs, as was the case elsewhere in the NDH. Resistance to communist leadership of the anti-Ustasha rebellion among the Serbs from Bosnia also developed in the form of the Chetnik movement and autonomous bands which were under command of Dragoljub Mihailović. Whereas the Partisans under Serb leadership were open to members of various nationalities, those in the Chetniks were hostile to Muslims and exclusively Serbian. The uprising in Bosnia and Herzegovina started by Serbs in many places were acts of retaliation against the Muslims, with thousands of them killed. A rebellion began in June 1941 in Herzegovina. On 27 July 1941, a Partisan-led uprising began in the area of Drvar and Bosansko Grahovo. It was a coordinated effort from both sides of the Una River in the territory of southeastern Lika and southwestern Bosanska, and succeeded in transferring key NDH territory under rebel control.

On 10 August in Stanulović, a mountain village, the Partisans formed the Kopaonik Partisan Detachment Headquarters. The area they controlled, consisting of nearby villages, was called the "Miners Republic" and lasted 42 days. The resistance fighters formally joined the ranks of the Partisans later on.

At the September 1941 Stolice conference, the unified name partisans and the red star as an identification symbol were adopted for all fighters led by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia.

In 1941, Partisan forces in Serbia and Montenegro had around 55,000 fighters, but only 4,500 succeeded to escape to Bosnia. On 21 December 1941 they formed the 1st Proletarian Assault Brigade (1. Proleterska Udarna Brigada) – the first regular Partisan military unit, capable of operating outside its local area. In 1942 Partisan detachments officially merged into the People's Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia (NOV i POJ) with an estimated 236,000 soldiers in December 1942.

Partisan numbers from Serbia would be diminished until 1943 when the Partisan movement gained upswing by spreading the fight against the axis. Increase of number of Partisans in Serbia, similarly to other republics, came partly in response to Tito's offer of amnesty to all collaborators on 17 August 1944. At that point tens of thousands of Chetniks switched sides to the Partisans. The amnesty would be offered again after German withdrawal from Belgrade on 21 November 1944 and on 15 January 1945.

Operations

Resistance and retaliation

The Partisans staged a guerrilla campaign which enjoyed gradually increased levels of success and support of the general populace, and succeeded in controlling large chunks of Yugoslav territory. These were managed via the "People's committees", organized to act as civilian governments in areas of the country controlled by the communists, even limited arms industries were set up. At the very beginning, Partisan forces were relatively small, poorly armed and without any infrastructure. They had two major advantages over other military and paramilitary formations in former Yugoslavia:

- A small but valuable cadre of Yugoslav volunteers in the Spanish Civil War who, unlike anyone else at the time, had experience with modern war fought in circumstances quite similar to those of World War II Yugoslavia

- They were founded on ideology rather than ethnicity, which meant the Partisans could expect at least some levels of support in any corner of the country, unlike other paramilitary formations whose support was limited to territories with Croat or Serb majorities. This allowed their units to be more mobile and fill their ranks with a larger pool of potential recruits.

Occupying and quisling forces, however, were quite aware of the Partisan threat, and attempted to destroy the resistance in what Yugoslav historiographers defined as seven major enemy offensives. These are:

- The First Enemy Offensive, the attack conducted by the Axis in autumn of 1941 against the "Republic of Užice", a liberated territory the Partisans established in western Serbia. In November 1941, German troops attacked and reoccupied this territory, with the majority of Partisan forces escaping towards Bosnia. It was during this offensive that tenuous collaboration between the Partisans and the royalist Chetnik movement broke down and turned into open hostility.

- The Second Enemy Offensive, the coordinated Axis attack conducted in January 1942 against Partisan forces in eastern Bosnia. The Partisan troops once again avoided encirclement and were forced to retreat over Igman mountain near Sarajevo.

- The Third Enemy Offensive, an offensive against Partisan forces in eastern Bosnia, Montenegro, Sandžak and Herzegovina which took place in the spring of 1942. It was known as Operation TRIO by the Germans, and again ended with a timely Partisan escape. This attack is mistakenly identified by some sources as the Battle of Kozara, which took place in the summer of 1942.

- The Fourth Enemy Offensive, against "Republic of Bihać", also known as the Battle of the Neretva or Fall Weiss (Case White), a conflict spanning the area between western Bosnia and northern Herzegovina, and culminating in the Partisan retreat over the Neretva river. It took place from January to April 1943.

- The Fifth Enemy Offensive, also known as the Battle of the Sutjeska or Fall Schwarz (Case Black). The operation immediately followed the Fourth Offensive and included a complete encirclement of Partisan forces in southeastern Bosnia and northern Montenegro in May and June 1943.

- The Sixth Enemy Offensive, a series of operations undertaken by the Wehrmacht and the Ustaše after the capitulation of Italy in an attempt to secure the Adriatic coast. It took place in late 1943 and early 1944.

- The Seventh Enemy Offensive, the final attack in western Bosnia in the second quarter of 1944, which included Operation Rösselsprung (Knight's Leap), an unsuccessful attempt to eliminate Tito and annihilate the leadership of the Partisan movement.

Partisans operated as a regular army that remained highly mobile across occupied Yugoslavia. Partisan units engaged in overt acts of resistance which led to significant reprisals against civilians by Axis forces. The killing of civilians discouraged the Chetniks from carrying out overt resistance, however the Partisans were not fazed and continued overt resistance which disrupted Axis forces, but led to significant civilian casualties.

Allied support

Later in the conflict the Partisans were able to win the moral, as well as limited material support of the western Allies, who until then had supported General Draža Mihailović's Chetnik Forces, but were finally convinced of their collaboration fighting by many military missions dispatched to both sides during the course of the war.

To gather intelligence, agents of the western Allies were infiltrated into both the Partisans and the Chetniks. The intelligence gathered by liaisons to the resistance groups was crucial to the success of supply missions and was the primary influence on Allied strategy in Yugoslavia. The search for intelligence ultimately resulted in the demise of the Chetniks and their eclipse by Tito's Partisans. In 1942, although supplies were limited, token support was sent equally to each. The new year would bring a change. The Germans were executing Operation Schwarz (the Fifth anti-Partisan offensive), one of a series of offensives aimed at the resistance fighters, when F.W.D. Deakin was sent by the British to gather information. On April 13, 1941, Winston Churchill sent his greetings to the Yugoslav people. In his greeting he stated:

His reports contained two important observations. The first was that the Partisans were courageous and aggressive in battling the German 1st Mountain and 104th Light Division, had suffered significant casualties, and required support. The second observation was that the entire German 1st Mountain Division had traveled from Russia by railway through Chetnik-controlled territory. British intercepts (ULTRA) of German message traffic confirmed Chetnik timidity. All in all, intelligence reports resulted in increased Allied interest in Yugoslavia air operations and shifted policy. In September 1943, at Churchill's request, Brigadier General Fitzroy Maclean was parachuted to Tito's headquarters near Drvar to serve as a permanent, formal liaison to the Partisans. While the Chetniks were still occasionally supplied, the Partisans received the bulk of all future support.

Thus, after the Tehran Conference the Partisans received official recognition as the legitimate national liberation force by the Allies, who subsequently set up the RAF Balkan Air Force (under the influence and suggestion of Brigadier-General Fitzroy Maclean) with the aim to provide increased supplies and tactical air support for Marshal Tito's Partisan forces. During a meeting with Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Combined Chiefs of Staff of 24 November 1943, Winston Churchill pointed out that:

Activities increase (1943–1945)

With Allied air support (Operation Flotsam) and assistance from the Red Army, in the second half of 1944 the Partisans turned their attention to Serbia, which had seen relatively little fighting since the fall of the Republic of Užice in 1941. On 20 October, the Red Army and the Partisans liberated Belgrade in a joint operation known as the Belgrade Offensive. At the onset of winter, the Partisans effectively controlled the entire eastern half of Yugoslavia – Serbia, Vardar Macedonia and Montenegro, as well as the Dalmatian coast.

In 1945, the Partisans, numbering over 800,000 strong defeated the Armed Forces of the Independent State of Croatia and the Wehrmacht, achieving a hard-fought breakthrough in the Syrmian front in late winter, taking Sarajevo in early April, and the rest of the NDH and Slovenia through mid-May. After taking Rijeka and Istria, which were part of Italy before the war, they beat the Allies to Trieste by two days. The "last battle of World War II in Europe", the Battle of Poljana, was fought between the Partisans and retreating Wehrmacht and quisling forces at Poljana, near Prevalje in Carinthia, on 14–15 May 1945.

Overview by post-war republic

Serbia

The Axis invasion led to the division of Yugoslavia between the Axis powers and the Independent State of Croatia. The largest part of Serbia was organized into the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia and as such it was the only example of military regime in occupied Europe. The Military Committee of the Provincial Committee of the Communist Party for Serbia was formed in mid-May 1941. The Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia arrived in Belgrade in late May, and this was of great importance for the development of the resistance in Yugoslavia. After their arrival, the Central Committee held conferences with local party officials. The decision for preparing the struggle in Serbia issued on June 23, 1941 at the meeting of the Provincial Committee for Serbia. On July 5, a Communist Party proclamation appeared that called upon the Serbian people to struggle against the invaders. Western Serbia was chosen as the base of the uprising, which later spread to other parts of Serbia. A short-lived republic was created in the liberated west, the first liberated territory in Europe. The uprising was suppressed by German forces by 29 November 1941. The Main National Liberation Committee for Serbia is believed to have been founded in Užice on 17 November 1941. It was the body of the Partisan resistance in Serbian territory.

The Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Serbia was held 9–12 November 1944.

Tito's post-war government built numerous monuments and memorials in Serbia after the war.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Serbian Partisan detachments entered Bosnian territory after the Operation Uzice which saw the Serbian uprising quelled. The Bosnian Partisans were heavily reduced during Operation Trio (1942) on the resistance in eastern Bosnia.

Croatia

The National Liberation Movement in Croatia was part of the anti-fascist National Liberational Movement in the Axis-occupied Yugoslavia which was the most effective anti-Nazi resistance movement led by Yugoslav revolutionary communists during the Second World War. NOP was under the leadership of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (KPJ) and supported by many others, with Croatian Peasant Party members contributing to it significantly. NOP units were able to temporarily or permanently liberate large parts of Croatia from occupying forces. Based on the NOP, the Federal Republic of Croatia was founded as a constituent of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia.

Services

Aside from ground forces, the Yugoslav Partisans were the only resistance movement in occupied Europe to employ significant air and naval forces.

Partisan Navy

Naval forces of the resistance were formed as early as 19 September 1942, when Partisans in Dalmatia formed their first naval unit made of fishing boats, which gradually evolved into a force able to engage the Italian Navy and Kriegsmarine and conduct complex amphibious operations. This event is considered to be the foundation of the Yugoslav Navy. At its peak during World War II, the Yugoslav Partisans' Navy commanded 9 or 10 armed ships, 30 patrol boats, close to 200 support ships, six coastal batteries, and several Partisan detachments on the islands, around 3,000 men. Their main base was the small port of Podgora, which was bombarded several times by Italian naval forces. On 26 October 1943, it was organized first into four, and later into six, Maritime Coastal Sectors (Pomorsko Obalni Sektor, POS). The task of the naval forces was to secure supremacy at sea, organize defense of coast and islands, and attack enemy sea traffic and forces on the islands and along the coasts.

Partisan Air Force

The Partisans gained an effective air force in May 1942, when the pilots of two aircraft belonging to the Air Force of the Independent State of Croatia (French-designed and Yugoslav-built Potez 25, and Breguet 19 biplanes, themselves formerly of the Royal Yugoslav Air Force), Franjo Kluz and Rudi Čajavec, defected to the Partisans in Bosnia. Later, these pilots used their aircraft against Axis forces in limited operations. Although short-lived due to a lack of infrastructure, this was the first instance of a resistance movement having its own air force. Later, the air force would be re-established and destroyed several times until its permanent institution. The Partisans later established a permanent air force by obtaining aircraft, equipment, and training from captured Axis aircraft, the British Royal Air Force (see BAF), and later the Soviet Air Force.

Composition

Yugoslav Partisans were predominantly Serb in composition into 1943. Also, it should be kept in mind that until the middle of the war the Partisans were in control of relatively large liberated areas only in parts of Bosnia. Over the entirety of the war according to the records of recipients of Partisan pensions from 1977, the ethnic composition of the Partisans was 53.0% Serb, 18.6% Croat, 9.2% Slovene, 5.5% Montenegrin, 3.5% Bosnian Muslim, and 2.7% Macedonian. Much of the remainder of the NOP's membership was made up of Albanians, Hungarians and those self-identifying as Yugoslavs. At the moment of the capitulation of Italy to the Allies, the Serbs and Croats were participating equally according to their respective population sizes in Yugoslavia as a whole. According to Tito, by May 1944, the ethnic composition of the Partisans was 44% Serb, 30% Croat, 10% Slovene, 5% Montenegrin, 2.5% Macedonian and 2.5% Bosnian Muslim. Italians were also in the army: more than 40,000 Italian fighters were in several military formations such as 9th Corps (Yugoslav Partisans), Partisan Battalion Pino Budicin, Partisan Division "Garibaldi" and Division Italia (Yugoslavia) later and others. Following the Soviet-Bulgarian offensive in Serbia and North Macedonia in the autumn of 1944, mass Partisan conscription of Serbs, Macedonians and eventually Kosovo Albanians increased. The number of Serbian Partisan brigades went up from 28 in June 1944 to 60 by the end of the year. In regional terms, the Partisan movement was therefore disproportionately west Yugoslav, particularly from Croatia, while until the autumn of 1944, Serbia's contribution was disproportionately small. During 1941 until September 1943 from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina 1,064 of Jews joined the Partisans, and largest part of Jews joined the Partisans after the capitulation of Italy in 1943. At the end of the war, 2,339 of Jewish Partisans from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina survived while 804 were killed. Most of the Jews who joined the Yugoslav Partisans were from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. According to Romano this number is 4,572; 1,318 of them were killed.

According to the Encyclopedia of the Holocaust of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum,

By April 1945, there were some 800,000 soldiers in the Partisan army. Composition by region (ethnicity is not taken into account) from late 1941 to late 1944 was as follows:

According to Fabijan Trgo in the summer of 1944 the National Liberation Army had about 350,000 soldiers in 39 divisions, which were grouped into 12 Corps. In September 1944 about 100,000 soldiers in 17 divisions were ready to enter the final phase of the battle for the liberation of Serbia, overall in all Yugoslav areas the National Liberation Army had about 400,000 armed soldiers. That is, 15 corps, ie 50 divisions, 2 operational groups, 16 independent brigades, 130 partisan detachments, the navy and the first aviation formations. At the beginning of 1945, the number of soldiers was about 600,000. On March 1, the Yugoslav Army had more than 800,000 soldiers, grouped in 63 divisions.

The Chetniks were a mainly Serb-oriented group and their Serb nationalism resulted in an inability to recruit or appeal to many non-Serbs. The Partisans played down communism in favour of a Popular Front approach which appealed to all Yugoslavs. In Bosnia, the Partisan rallying cry was for a country which was to be neither Serbian nor Croatian nor Muslim, but instead to be free and brotherly in which full equality of all groups would be ensured. Nevertheless, Serbs remained the dominant ethnic group in the Yugoslav Partisans throughout the war. Italian collaboration with Chetniks in northern Dalmatia resulted in atrocities which further galvanized support for the Partisans among Dalmatian Croats. Chetnik attacks on Gata, near Split, resulted in the slaughter of some 200 Croatian civilians.

In particular, Mussolini's policy of forced Italianization ensured the first significant number of Croats joining the Partisans in late 1941. In other areas, recruitment of Croats was hindered by some Serbs' tendency to view the organisation as exclusively Serb, rejecting non-Serb members and raiding the villages of their Croat neighbours. A group of Jewish youths from Sarajevo attempted to join a Partisan detachment in Kalinovnik, but the Serbian Partisans turned them back to Sarajevo, where many were captured by the Axis forces and perished. Attacks from Croatian Ustaše on the Serbian population was considered to be one of the important reasons for the rise of guerrilla activities, thus aiding an ever-growing Partisan resistance. Following the capitulation of Italy and subsequent Belgrade Offensive, many members of the Ustaše joined the partisans.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

At the beginning of the war, the dominant Serb composition of the Partisan rank and file and alliance with the Chetniks, who were engaged in atrocities and killing of Croat and Muslim civilians, forced Croats and Muslims not to join the Bosnian Partisans. Until early 1942, the Partisans in Bosnia and Herzegovina, who were almost exclusively Serbs, cooperated closely with the Chetniks, and some Partisans in eastern Herzegovina and western Bosnia refused to accept Muslims into their ranks. For many Muslims, the behavior of these Serb Partisans towards them meant that there was little difference for them between the Partisans and Chetniks. However, in some areas of Bosnia and Herzegovina the Partisans were successful in attracting both Muslims and Croats from the beginning, notably in the Kozara Mountain area in north-west Bosnia and the Romanija Mountain area near Sarajevo. In the Kozara area, Muslims and Croats made up 25 percent of Partisan strength by the end of 1941.

According to Hoare, by late 1943, 70% of the Partisans in Bosnia and Herzegovina were Serb and 30% were Croat and Muslim. At the end of 1977, Bosnian recipients of war pensions were 64.1% Serb, 23% Muslim, and 8.8% Croat.

Croatia

In 1941–42, the majority of Partisans in Croatia were Serbs. However, by October 1943, the majority were Croats. This change was partly due to the decision of a key Croatian Peasant Party member, Božidar Magovac, to join the Partisans in June 1943, and partly due to the surrender of Italy. At the moment of the capitulation of Italy to the Allies the Serbs and Croats were participating equally according to their respective population sizes in Yugoslavia as a whole. According to Goldstein, among Croatian partisans at the end of 1941, 77% were Serbs and 21.5% were Croats, and others as well as unknown nationalities. The percentage of Croats in the Partisans had increased to 32% by August 1942, and 34% by September 1943. After the capitulation of Italy, it increased further. At the end of 1944 there were 60.4% Croats, 28.6% Serbs and 11% of other nationalities (2.8% Muslims, Slovenes, Montenegrins, Italians, Hungarians, Czechs, Jews and Germans) in Croatian partisan units. According to Ivo Banac, the Croatian Partisan movement in the second half of 1944 had about 150,000 combatants under arms, while 100,070 were in operative units where Croats numbered 60,703 (60.7%), Serbs 24,528 (24.5%), Slovenes 5,113 (5.1%), and others. The Serb contribution to Croatian Partisans represented more than their proportion of the local population.

Croatian Partisans were integral to overall Yugoslav Partisans with ethnic Croats in prominent positions in the movement since the very beginning of the war; According to some researchers writing during 1990s, like Cohen, by the end of 1943, Croatia proper, with 24% of the Yugoslav population, provided more Partisans than Serbia, Montenegro, Slovenia and Macedonia combined (though not more than Bosnia and Herzegovina). In early 1943 Partisans took steps to establish ZAVNOH (National Anti-Fascist Council of the People's Liberation of Croatia) to act as a parliamentary body for all of Croatia – the only one of its kind in occupied Europe. ZAVNOH held three plenary sessions during the war in areas which remained surrounded by Axis troops. At its fourth and last session, held on 24–25 July 1945 in Zagreb, ZAVNOH proclaimed itself as the Croatian Parliament or Sabor.

By the end of 1941 in the territory of the NDH, Serbs comprised approximately one-third of the population but about 95% of all Partisans. This numerical dominance lessened later, but until 1943 Serbs formed a majority of Partisans in Croatia (including Dalmatia). Territories in Croatia proper with a substantial number of Serb inhabitants (Lika, Banija, Kordun) formed the most important source of manpower for the Partisans. In May 1941 the Ustasha regime ceded northern Dalmatia to Fascist Italy, which caused increasingly massive support for the Partisans among the Croats of Dalmatia. In other parts of Croatia Croat support toward the Partisans gradually increased due to Ustasha and Axis violence and misrule, but much more slowly than in Dalmatia. There were only 1,492 Partisans from Serbia out of the 22,148 Partisans of Tito's Main Operational Group (Serbo-Croatian: Glavna operativna grupa) at the Battle of the River Sutjeska in June 1943, and 8,925 were from Croatia (of which 5,195 were from Dalmatia), but in ethnic terms, 11,851 were Serbs beside 5,220 Croats. At the end of 1943 all 13 Dalmatian Partisan brigades had a Croat majority, but among the 25 Partisan brigades from Croatian proper (without Dalmatia) only 7 had a Croat majority (17 had a Serb majority and one had a Czech majority). According to historians Tvrtko Jakovina and Davor Marijan the main reason for massive participation of Croats in Battle of the Sutjeska in June 1943 was ongoing terror of Italian fascists.

According to Tito, one-quarter of Zagreb's population (i.e. more than 50,000 citizens) participated in the Partisan struggle during which over 20,000 of them were killed (half of them as active fighters). As Partisan combatants 4,709 citizens of Zagreb were killed while 15,129 were killed in Ustasha and Nazi prisons and concentration camps, and another 6,500 were killed during anti-insurgency operations.

In the final offensive for the liberation of Yugoslavia, from Croatia was engaged 165,000 soldiers mostly for the liberation of Croatia. On Croatian territory after 30 November 1944 in combat with the enemy participated 5 corps, 15 divisions, 54 brigades and 35 Partisan detachments, a total of 121,341 soldiers (117,112 men and 4239 woman) which at the end of 1944 made up about third of the entire armed forces of the National Liberation Army. At the same time, on the territory of Croatia there was 340,000 of German soldiers, 150,000 of Ustasha and Home Guard soldiers while the Chetniks at beginning of 1945 withdrew towards Slovenia. According to the ethnic composition of Partisans, most were Croats 73,327 or 60.4%, followed by Serbs 34,753 or 28.6%, Muslims 3,316 or 2.8%, Jews 284 or 0.3% and Slovenes, Montenegrins and others with 9,671 or 8.0%, (number of Partisans and ethnic composition does not include 9 brigades which were engaged outside of Croatia).

Serbia

By the end of September 1941, 24 detachments have been established with approximately 14,000 soldiers. By the end of 1943, 97 Partisan brigades existed overall, while in the eastern parts of Yugoslavia (Vojvodina, Serbia, Montenegro, Kosovo and Macedonia) 18 Partisan brigades existed. In Serbia during the spring and summer of 1944, many Chetnik deserters and prisoners joined Partisans units. When the Soviets liberated Serbia at the end of 1944, mass Partisan mobilization of Serbians, Macedonians and eventually Kosovo Albanians began, which led to a balanced geographical contribution between the eastern and western Yugoslav Partisan movements. Serbia’s contribution to the Partisan movement prior to the autumn of 1944 was disproportionately small. At the end of September 1944, Serbia had about 70,000 soldiers under the command of the Main Staff of Serbia of which in the 13th Corps were about 30,000 soldiers, in the 14th Corps 32,463 soldiers and in the 2nd Proletarian Division 4,600 soldiers.

Slovenia

During World War II, Slovenia was in a unique situation in Europe. Only Greece shared its experience of being trisected; however, Slovenia was the only country that experienced a further step – absorption and annexation into neighboring Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and Hungary. As the very existence of the Slovene nation was threatened, the Slovene support for the Partisan movement was much more solid than in Croatia or Serbia. An emphasis on the defence of ethnic identity was shown by naming the troops after important Slovene poets and writers, following the example of the Ivan Cankar battalion.

At the very beginning, the Partisan forces were small, poorly armed and without any infrastructure. However, the Spanish Civil War veterans amongst them had some experience with guerrilla warfare. The Partisan movement in Slovenia functioned as the military arm of the Liberation Front of the Slovene Nation, an Anti-Fascist resistance platform established in the Province of Ljubljana on 26 April 1941, which originally consisted of multiple groups of left wing orientation, most notable being Communist Party and Christian Socialists. During the course of the war, the influence of the Communist Party of Slovenia started to grow, until its supremacy was officially sanctioned in the Dolomiti Declaration of 1 March 1943. Some of the members of Liberation Front and partisans were ex-members of the TIGR resistance movement.

Representatives of all political groups in Liberation Front participated in Supreme Plenum of Liberation Front, which led the resistance efforts in Slovenia. Supreme Plenum was active until 3 October 1943 when, at the Assembly of the Slovenian Nation's Delegates in Kočevje, the 120-member Liberation Front Plenum was elected as the supreme body of the Slovenian Liberation Front. The plenum also functioned as Slovenian National Liberation Committee, the supreme authority in Slovenia. Some historians consider the Kočevje Assembly to be the first Slovene elected parliament and Slovene Partisans as its representatives also participated on 2nd session of the AVNOJ and were instrumental in adding the self-determination clause to the resolution on the establishment of a new federal Yugoslavia. The Liberation Front Plenum was renamed the Slovenian National Liberation Council at the conference in Črnomelj on 19 February 1944 and transformed into the Slovenian parliament.

The Slovene Partisans retained their specific organizational structure and Slovene language as the commanding language until the last months of World War II, when their language was removed as the commanding language. From 1942 till after 1944, they wore the Triglavka cap, which was then gradually replaced with the Titovka cap as part of their uniform. In March 1945, the Slovene Partisan Units were officially merged with the Yugoslav Army and thus ceased to exist as a separate formation.

The partisan activities in Slovenia started in 1941 and were independent of Tito's partisans in the south. In autumn 1942, Tito attempted for the first time to control the Slovene resistance movement. Arso Jovanović, a leading Yugoslav communist who was sent from Tito's Supreme Command of Yugoslav partisan resistance, ended his mission to establish central control over the Slovene partisans unsuccessfully in April 1943. The merger of the Slovene Partisans with Tito's forces happened in 1944.

In December 1943, Franja Partisan Hospital was built in difficult and rugged terrain, only a few hours from Austria and the central parts of Germany. The partisans broadcast their own radio program called Radio Kričač, the location of which never became known to occupying forces, although the receiver antennas from the local population had been confiscated.

Casualties

Despite their success, the Partisans suffered heavy casualties throughout the war. The table depicts Partisan losses, 7 July 1941 – 16 May 1945:

According to Ivo Goldstein, 82,000 Serbs and 42,000 Croats were killed on NDH territory as partisan combatants.

Rescue operations

The Partisans were responsible for the successful and sustained evacuation of downed Allied airmen from the Balkans. For example, between 1 January and 15 October 1944, according to statistics compiled by the US Air Force Air Crew Rescue Unit, 1,152 American airmen were airlifted from Yugoslavia, 795 with Partisan assistance and 356 with the help of the Chetniks. Yugoslav Partisans in Slovene territory rescued 303 American airmen, 389 British airmen and prisoners of war, and 120 French and other prisoners of war and slave laborers.

The Partisans also assisted hundreds of Allied soldiers who succeeded in escaping from German POW camps (mostly in southern Austria) throughout the war, but especially from 1943 to 1945. These were transported across Slovenia, from where many were airlifted from Semič, while others made the longer overland trek down through Croatia for a boat passage to Bari in Italy. In the spring of 1944, the British military mission in Slovenia reported that there was a "steady, slow trickle" of escapes from these camps. They were being assisted by local civilians, and on contacting Partisans on the general line of the River Drava, they were able to make their way to safety with Partisan guides.

Raid at Ožbalt

A total of 132 Allied prisoners of war were rescued from the Germans by the Partisans in a single operation in August 1944 in what is known as the Raid at Ožbalt. In June 1944, the Allied escape organization began to take an active interest in assisting prisoners from camps in southern Austria and evacuating them through Yugoslavia. A post of the Allied mission in northern Slovenia had found that at Ožbalt, just on the Austrian side of the border, about 50 km (31 mi) from Maribor, there was a poorly guarded working camp from which a raid by Slovene Partisans could free all the prisoners. Over 100 POWs were transported from Stalag XVIII-D at Maribor to Ožbalt each morning to do railway maintenance work, and returned to their quarters in the evening. Contact was made between Partisans and the prisoners with the result that at the end of August a group of seven slipped away past a sleeping guard at 15:00, and at 21:00 the men were celebrating with the Partisans in a village, 8 km (5.0 mi) away on the Yugoslav side of the border.

The seven escapees arranged with the Partisans for the rest of the camp to be freed the following day. Next morning, the seven returned with about a hundred Partisans to await the arrival of the work-party by the usual train. As soon as work had begun the Partisans, to quote a New Zealand eye-witness, "swooped down the hillside and disarmed the eighteen guards". In a short time prisoners, guards, and civilian overseers were being escorted along the route used by the first seven prisoners the previous evening. At the first headquarters camp reached, details were taken of the total of 132 escaped prisoners for transmission by radio to England. Progress along the evacuation route south was difficult, as German patrols were very active. A night ambush by one such patrol caused the loss of two prisoners and two of the escort. Eventually they reached Semič, in White Carniola, Slovenia, which was a Partisan base catering for POWs. They were flown across to Bari on 21 September 1944 from the airport of Otok near Gradac.

Post-war

SFR Yugoslavia was one of only two European countries that were largely liberated by its own forces during World War II. It received significant assistance from the Soviet Union during the liberation of Serbia, and substantial assistance from the Balkan Air Force from mid-1944, but only limited assistance, mainly from the British, prior to 1944. At the end of the war no foreign troops were stationed on its soil. Partly as a result, the country found itself halfway between the two camps at the onset of the Cold War.

In 1947–48, the Soviet Union attempted to command obedience from Yugoslavia, primarily on issues of foreign policy, which resulted in the Tito–Stalin split and almost ignited an armed conflict. A period of very cold relations with the Soviet Union followed, during which the U.S. and the UK considered courting Yugoslavia into the newly formed NATO. This however changed in 1953 with the Trieste crisis, a tense dispute between Yugoslavia and the Western Allies over the eventual Yugoslav-Italian border (see Free Territory of Trieste), and with Yugoslav-Soviet reconciliation in 1956. This ambivalent position at the start of the Cold War matured into the non-aligned foreign policy which Yugoslavia actively espoused until its dissolution.

Atrocities

The Partisans massacred civilians during and after the war. On 27 July 1941, Partisan-led units massacred around 100 Croat civilians in Bosansko Grahovo and 300 in Trubar during the Drvar uprising against the NDH. Between 5–8 September 1941, some 1,000–3,000 Muslim civilians and soldiers, including 100 Croats were massacred by the Partisan Drvar Brigade. A number of Partisan units, and the local population in some areas, engaged in mass murder in the immediate postwar period against POWs and other perceived Axis sympathizers, collaborators, and/or fascists along with their relatives, including children. These infamous massacres include the Foibe massacres, Tezno massacre, Macelj massacre, Kočevski Rog massacre, Barbara Pit massacre and the communist purges in Serbia in 1944–45.

The Bleiburg repatriations of retreating columns of the Armed Forces of the Independent State of Croatia, Chetnik and Slovene Home Guard troops, thousands of civilians heading or retreating towards Austria to surrender to western Allied forces, resulted in mass executions with tens of thousands of victims. The "foibe massacres" draw their name from the "foibe" pits in which Croatian Partisans of the 8th Dalmatian Corps (often along with groups of angry civilian locals) shot Italian fascists, and suspected collaborationists and/or separatists. According to a mixed Slovene-Italian historical commission established in 1993, which investigated only on what happened in places included in present-day Italy and Slovenia, the killings seemed to proceed from endeavors to remove persons linked with fascism (regardless of their personal responsibility), and endeavors to carry out mass executions of real, potential or only alleged opponents of the communist government. The 1944–1945 killings in Bačka were similar in nature and entailed the killing of suspected Hungarian, German and Serbian fascists, and their suspected affiliates, without regard to their personal responsibility. During this purge, a large number of civilians from the associated ethnic group were also killed.[page needed]

The Partisans did not have an official agenda of liquidating their enemies and their cardinal ideal was the "brotherhood and unity" of all Yugoslav nations (the phrase became the motto for the new Yugoslavia). The country suffered between 900,000 and 1,150,000 civilian and military dead during the Axis occupation. Between 80,000 and 100,000 people were killed in the partisan purges and at least 30,000 people were killed in the Bleiburg killings, according to Marcus Tanner in his work, Croatia: a Nation Forged in War.[full citation needed]

This chapter of Partisan history was a taboo subject for conversation in the SFR Yugoslavia until the late 1980s, and as a result, decades of official silence created a reaction in the form of numerous data manipulation for nationalist propaganda purposes.

Equipment

The first small arms for the Partisans were acquired from the defeated Royal Yugoslav Army, like the M24 Mauser rifle. Throughout the war the Partisans used any weapons they could find, mostly weapons captured from the Germans, Italians, Army of the NDH, Ustaše and the Chetniks, such as the Karabiner 98k rifle, MP 40 submachine gun, MG 34 machine gun, Carcano rifle and carbine, and Beretta submachine gun. The other way that the Partisans acquired weapons was from supplies given to them by the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom, including the PPSh-41 and the Sten MKII submachine guns respectively. Additionally, Partisan workshops created their own weapons modelled on factory-made weapons already in use, including the so-called "Partisan rifle" and the anti-tank "Partisan mortar".

Ranks

Officer ranks

The rank insignia of commissioned officers.

| Rank group | General / flag officers | Senior officers | Junior officers | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| June 1941–December 1942 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Komandant brigade | Komendant odrede | Komandant bataljona | Komandir čete | |||||||||||||||||||||

| December 1942–April 1943 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Komandant glavnog štaba | Komandant operative zone | Zamenik operative komandanta zone | Komandant brigade | Načelnik štaba brigade | Zamenik komandanta brigade | Komendant odrede | Zamenik komendanta odrede | Načelnik štaba odrede | Komandant bataljona | Zamenik komandanta bataljona | Komandir čete | |||||||||||||

| May 1943–May 1945 |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | |||||||||||||

| Maršal Jugoslavije | General-pukovnik | General-lajtant | General-major | Pukovnik | Potpukovnik | Major | Kapetan | Poručnik | Potporučnik | Zastavnik | ||||||||||||||

| Rank group | General / flag officers | Senior officers | Junior officers | |||||||||||||||||||||

Other ranks

The rank insignia of non-commissioned officers and enlisted personnel.

| Rank group | Senior NCOs | Junior NCOs | Enlisted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| June 1941–December 1942 | No insignia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vodnik | Desetar | Borac | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| December 1942–April 1943 | No insignia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zamenik komandira čete | Vodnik | Desetar | Borac | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| May 1943–May 1945 |  |  |  |  | No insignia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stariji vodnik | Vodnik | Mlađi vodnik | Desetar | Vojnik | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank group | Senior NCOs | Junior NCOs | Enlisted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Women

The Yugoslav Partisans mobilized many women. The Yugoslav National Liberation Movement claimed 6,000,000 civilian supporters; its two million women formed the Antifascist Front of Women (AFŽ), in which the revolutionary coexisted with the traditional. The AFŽ managed schools, hospitals and even local governments. About 100,000 women served with 600,000 men in Tito's Yugoslav National Liberation Army. It stressed its dedication to women's rights and gender equality and used the imagery of traditional folklore heroines to attract and legitimize the partizanka (pl. partizanke; Partisan Woman). Members included figures such as Judita Alargić.

After the war, traditional gender roles were reinstated, but Yugoslavia is unique as its historians paid extensive attention to women's roles in the resistance, until the country broke up in the 1990s. Then the memory of the women soldiers faded away.

Partisan legacy

Political

The Partisan legacy is the subject of considerable debate and controversy due to the rise of ethnic nationalism in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Historical revisionism following the breakup of Yugoslavia has rendered the movement ideologically incompatible within the post-communist sociopolitical framework. This revisionist historiography has caused the Partisans' role in World War II to be generally ignored, disparaged or attacked within successor states.

Despite social changes commemorative tributes to the Partisan struggle are still observed throughout the former Yugoslavia, and are attended by veteran associations, descendants, yugo-nostalgics, Titoists, leftists and sympathisers.

The successor branches of the former Association of War Veterans of the People's Liberation War (SUBNOR), represent Partisan veterans in each republic and lobby against political and legal rehabilitation of war collaborators, along with efforts to renamed streets and public squares. These organisation's also maintain monuments and memorials dedicated to the People's Liberation War and anti-fascism in each respective nation.

Cultural

According to Vladimir Dedijer, more than 40,000 works of folk poetry were inspired by the Partisans.